Steel Wrapped Silk

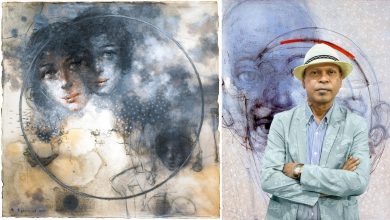

Steel Wrapped Silk Tayeba Begum Lipi’s art demands to be seen. It’s not the kind of art that asks for polite applause or quiet reflection; it challenges the viewer to confront uncomfortable truths about the roles of women in society. What happens when the softness of the female body is made harsh? What if traditional symbols of femininity—like wedding dresses or undergarments—are transformed into objects that speak of violence, control, and resistance? Her work doesn’t just ask these questions; it answers them boldly, with layers of meaning that explode in every piece. Born in 1969 in Gaibandha, Bangladesh, her artistic journey has taken her far beyond the borders of her homeland, but her work remains deeply rooted in the struggles faced by women in her country and beyond. Her art is as dynamic as the issues she explores—spanning sculptures, videos, Steel Wrapped Silk paintings, and installations.

Text: Rezwana Rashid Siddiquee

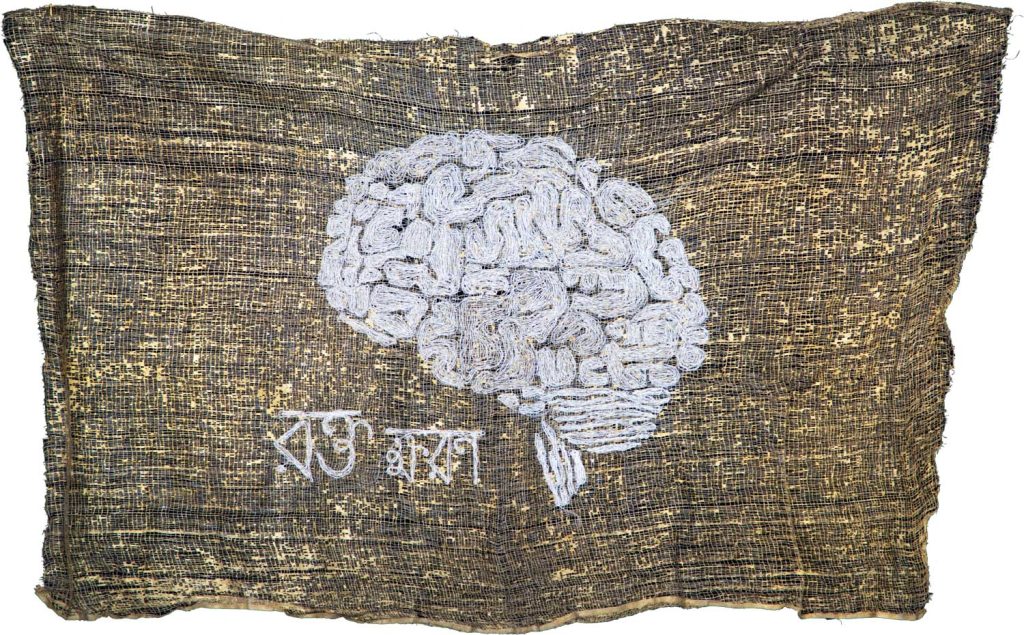

Across all of these forms,Tayeba Begum Lipi’s creations interrogate gender, identity, and societal expectations, particularly regarding the female body.

But perhaps more powerfully, she creates art that asks for nothing less than an awakening from the viewer.

Her background in art began at the University of Dhaka, where she completed a Master of Fine Arts in Drawing and Painting in 1993. From there, she went on to establish herself as one of Bangladesh’s most significant contemporary artists. She has exhibited in galleries and museums worldwide, from the Shanghai Modern Art Museum in China to the Birmingham Museum of Art in Alabama. In 2003, she earned the Grand Prize at the 11th Asian Art Biennale in Dhaka, cementing her place as an artist whose work transcends borders and speaks universally.

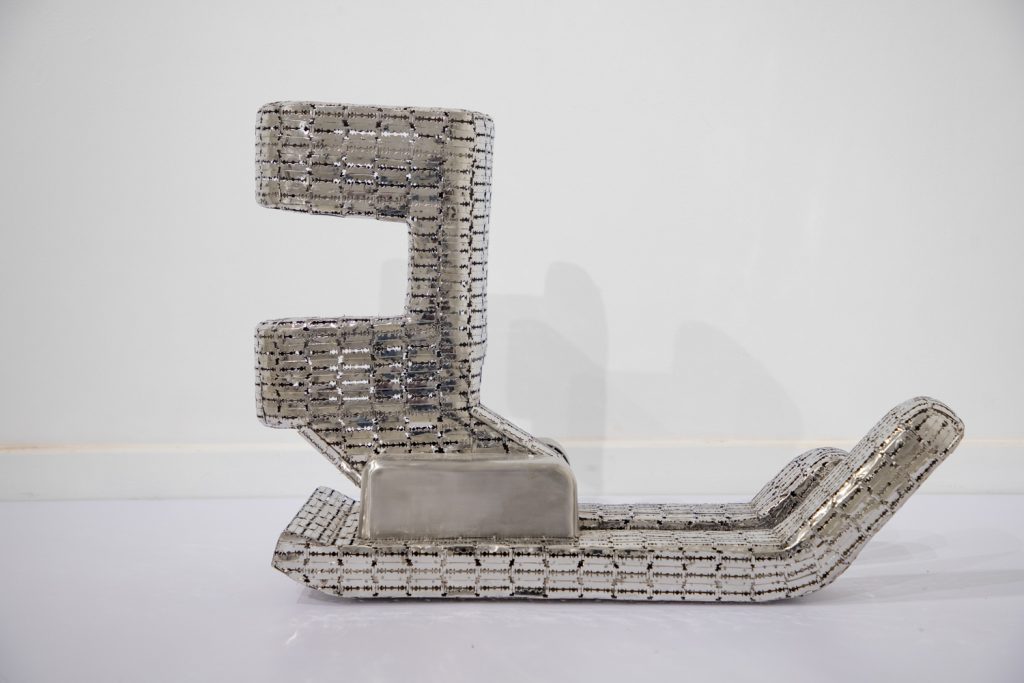

But what sets her apart from many other artists is the deep, provocative nature of her work. Take, for example, Bizarre and Beautiful (2011)—an installation of female undergarments made not of soft cotton or lace, but of stainless steel razor blades. What could be more jarring than this? The blades, cold and unforgiving, contrast sharply with the delicate, intimate associations we usually have with women’s clothing. They raise questions about the violent realities of womanhood. “The work is a visual punch in the gut, and the viewers are made to think about the harm that is often inflicted on women, even when they are perceived as the most vulnerable.In Tayeba Begum Lipi’s world, the soft and sensual become dangerous, the beautiful becomes bizarre, and women’s bodies—so often seen as sites of care—become objects of resistance.

Her work is also notable for the way it embraces contradictions. She doesn’t shy away from the complexities of gender, and she doesn’t settle for easy answers Steel Wrapped Silk

One of her most striking pieces is the video I Wed Myself (2010), in which she is portrayed simultaneously as both bride and groom by Lipi. She wears the traditional wedding makeup and attire of a woman about to marry, but then, in a surprising turn, she crops her hair and adds a mustache, completing the transformation into a male figure. The juxtaposition of these two roles within a single frame asks viewers to question the rigid categories of gender. Can we be both? Can we surpass the definitions society imposes on us? In her portrayal, she challenges the viewer to see gender not as a binary, but as a spectrum—fluid and malleable, not fixed.

In Toys Watching Toys (2002), a collaborative exhibition with her husband, Mahbubur Rahman, Tayeba Begum Lipi placed mannequins dressed in burqas, with fiberglass casts of her own head, facing a self-portrait of herself, wearing makeup. This powerful installation contrasted traditional religious modesty with modern individual freedom, sparking a conversation about the societal pressures women face to conform to specific roles, while denying them the space to express their true identities. These themes of identity, restriction, and resistance are central to Lipi’s work, and they echo particularly within the cultural context of Bangladesh.

As a country where historical, cultural, and religious norms continue to dictate the roles women are expected to play, Lipi’s art offers a critique of these forces

Through her provocative use of materials and her exploration of gender, she exposes the societal contradictions that shape women’s lives. The choice of materials—safety pins, razor blades, and stainless steel—are not random. They are deliberate, chosen to convey both the violence women endure and the tools that are used to control their bodies.

But her work is not just about confrontation or anger; it is also about empowerment. Her art channels the strength and resilience of the women who have shaped her life. Inspired by the powerful women in her family and community, Lipi’s creations often honor their courage while also questioning the roles they were forced to play.

In 2002, Lipi co-founded the Britto Arts Trust, Bangladesh’s first artist-run platform for alternative arts. This initiative has had a transformative impact on the local art scene, providing a space for emerging artists to showcase their work and engage with international audiences.

Lipi’s work has also been featured at prestigious international events, including the Venice Biennale in 2011, where she was the commissioner for the Bangladesh Pavilion. Her presence at these global stages has helped to bring the voices of Bangladeshi artists to the international spotlight, Steel Wrapped Silk challenging the way the world sees not only art but also the social issues that often remain hidden in the shadows. With solo exhibitions like Feminine (2007) and No One Home (2015), Lipi continues to explore the themes of identity and gender.

Her art pushes boundaries and sparks conversations that transcend the gallery walls.

She invites the viewer into a space of reflection, forcing them to question their own assumptions about gender, identity, and societal norms. In a world where women are still fighting for agency over their bodies and their lives, Lipi’s work is not just relevant—it’s urgent.

Steel Wrapped Silk Tayeba Begum Lipi e is a catalyst for change. Through her art, she demands that we see women’s lives not as passive narratives but as active, complex, and sometimes painful stories.We are reminded that art can be a powerful tool for social change, and we are asked to confront uncomfortable truths and reconsider the roles we are given. In doing so, a space is created where women’s voices can be heard, loud and clear.