The Evolution of art

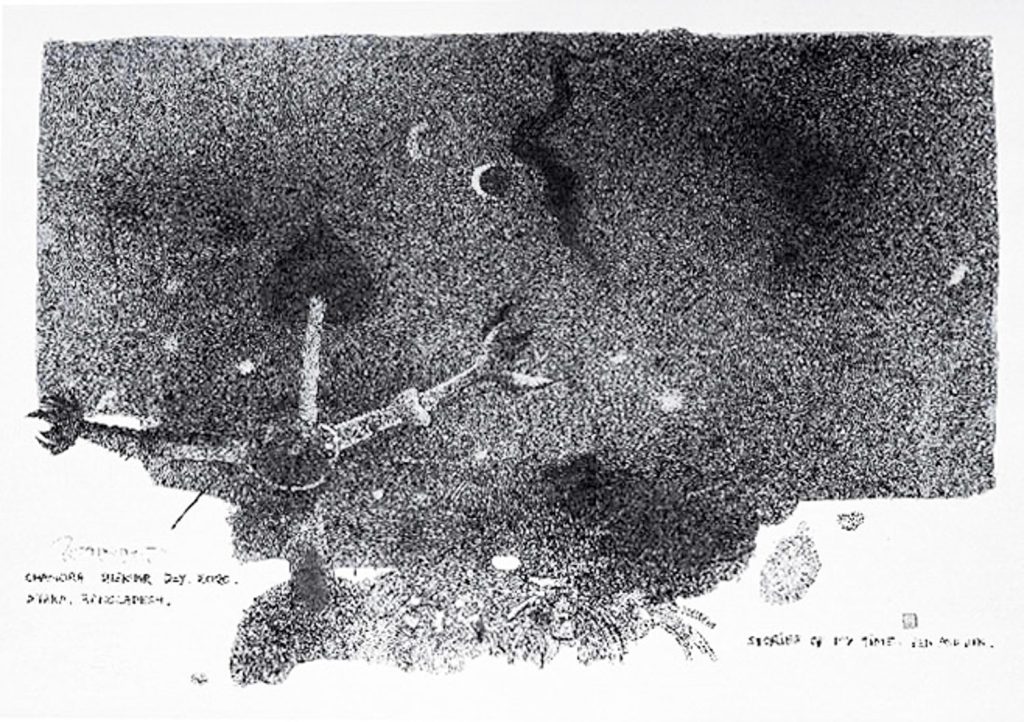

Chandra Shekhar Dey’s artistic journey, spanning nearly seven decades, began in Chittagong during a bygone era. “I was born on Jubilee Road, near the New Market of Chittagong city,” Dey recalls. “My school, Municipal Primary and High School, was right beside that. I came to Dhaka to enroll in the art college.”

The man spoke of a life lived and a life learned, “With art, your teachers leave an impact,” Dey reflects. “Almost all the teachers I had were from West Bengal, Kolkata-based. Because the British regime established the art college, the curriculum in my time was a mix of British and Indian influences. After the partition of India and Pakistan, they came to Dhaka. The first art school was established in Nawabpur and moved around until the government allocated a place in Shahbagh, where it remains today as part of Dhaka University.

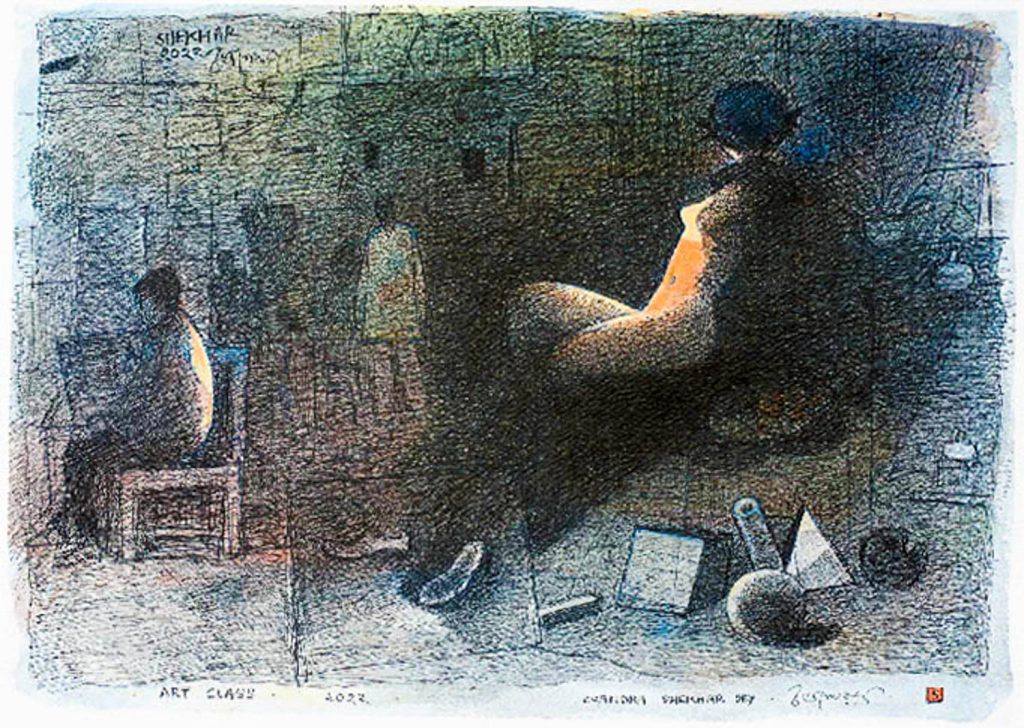

At what is now the Faculty of Fine Art at Dhaka University, Chandra Shekhar Dey was taught watercolour, pencil drawing, sketching, and composition. A memory as vivid as his work, the veteran artist still remembers the rigorous schedule,”We had classes from 10 AM to 5 PM, with lots of extra work for assignments—figure drawing, sketches, watercolours. That’s when I actually learned the concept behind art.”

Chandra Shekhar Dey notes that the history of modern day Bangladesh wasn’t always as favourable to art.

“Before the 1971 war, there used to be the Pakistan Art Council. Every district had either a Pakistan district library, or an art council. In place of where Shilpakala is now, there used to be a circular building. In what is now Bangladesh, art wasn’t something well known or understood by the masses.” Dey recounted a striking anecdote, “A prime example of that is that, in that building there was an exhibition by a great, like Picasso. His original prints were there, but barely a soul went. When we went to visit the exhibit— we were in shock at the sight. A goat had breached the premises, broken a frame and was pulling out the canvas to eat it. There wasn’t even one guard.” Despite these challenges, Dey participated in annual exhibitions at his college, receiving recognition and awards. His first solo exhibition was a significant milestone. “There was only one gallery in the entirety of Bangladesh, the Art Ensemble and Desh Gallery. The building was actually owned by a Pakistani family, they donated the space to be used as a gallery. It was the building on the opposite side of the BDR entrance. Because it was a living space, the gallery was situated in what was built as a living room.” he explains.

“The distance between the rich and the poor was so vast that it was nerve-racking to visit the gallery. Only the unimaginably rich and powerful visited.”

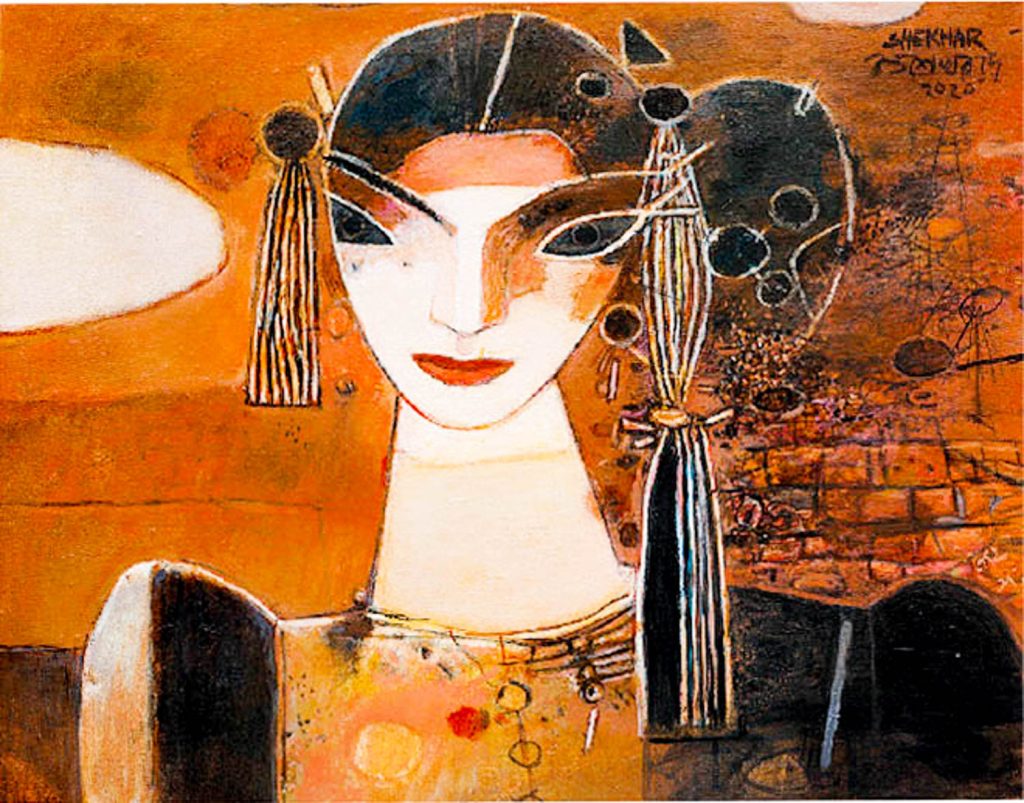

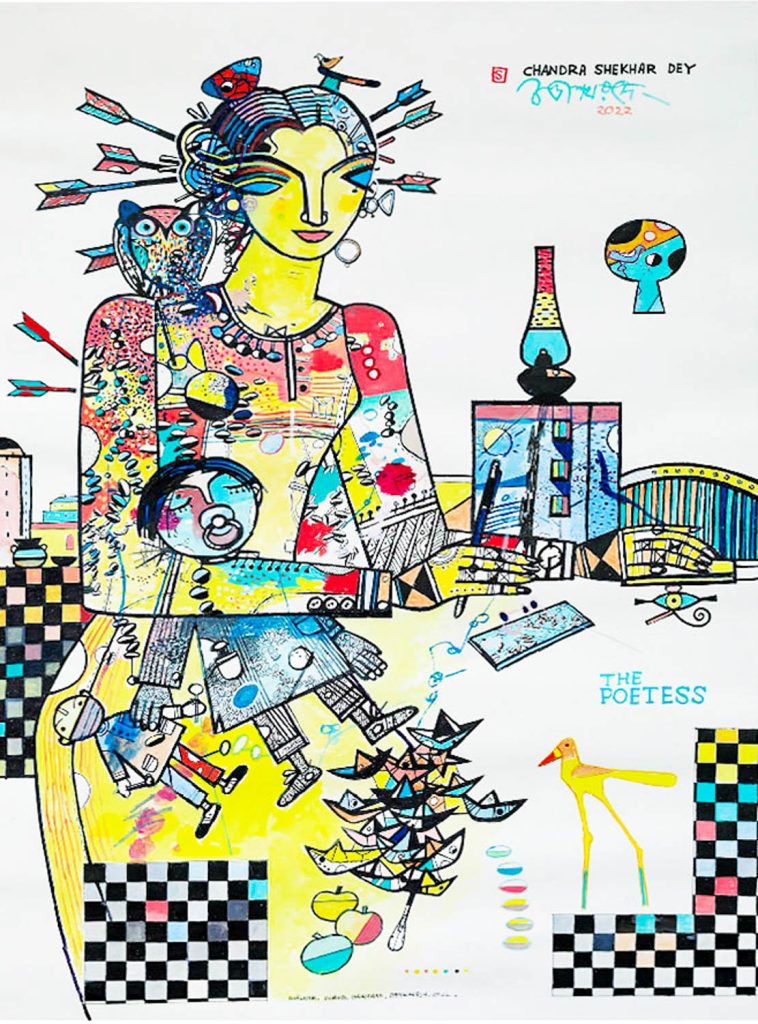

Dey’s second exhibition at Gallery 21, owned and orchestrated by one of his students, Subrana. “She randomly showed up at my home one day and told me, ‘Sir, I want to take these artworks with me to exhibit.’ I was completely unprepared, but she set up the exhibition with whatever I had on hand,” he says. After a hiatus of 33 years, Dey exhibited at Gallery Kaya in 2024. “I don’t have the mental, physical, or logistical elements to exhibit regularly,” he explains.

“Whatever I make, I sell off to run my household or to buy more art materials. But I am very glad this exhibition is happening. People can finally put a face to my name and to my art.”

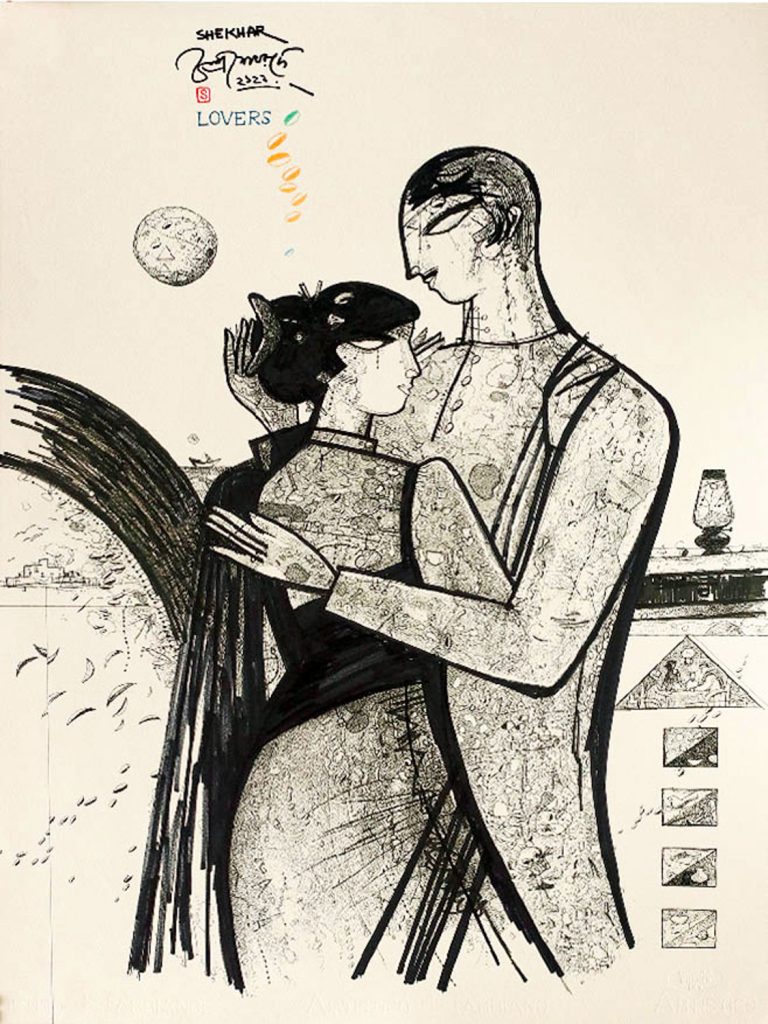

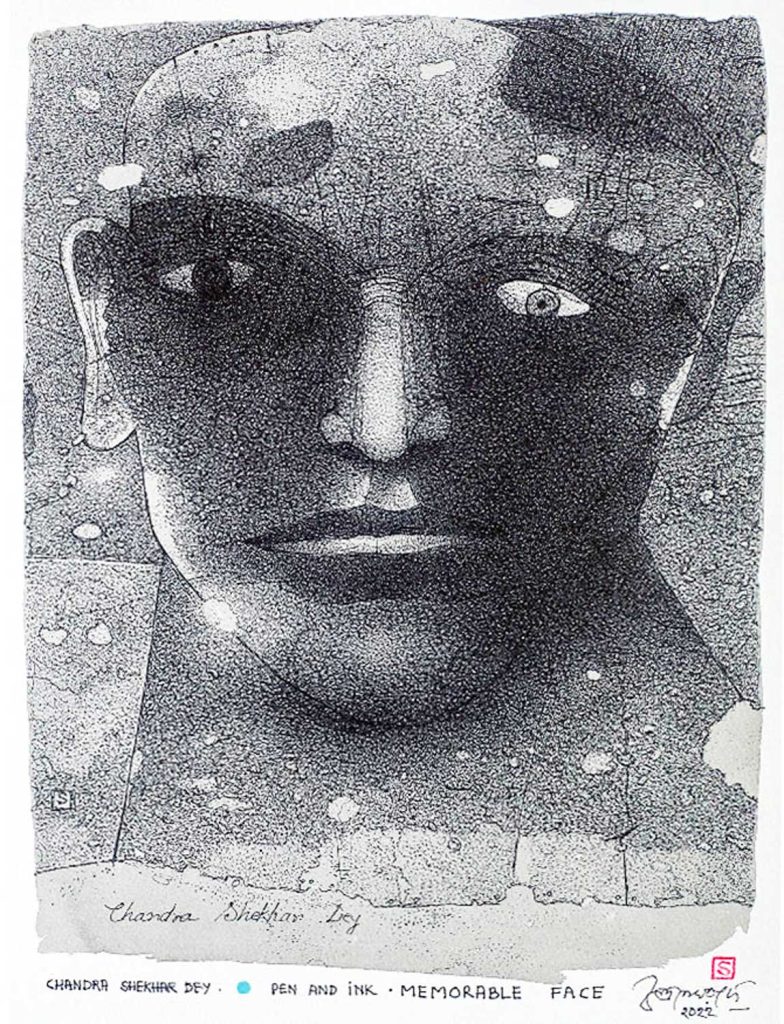

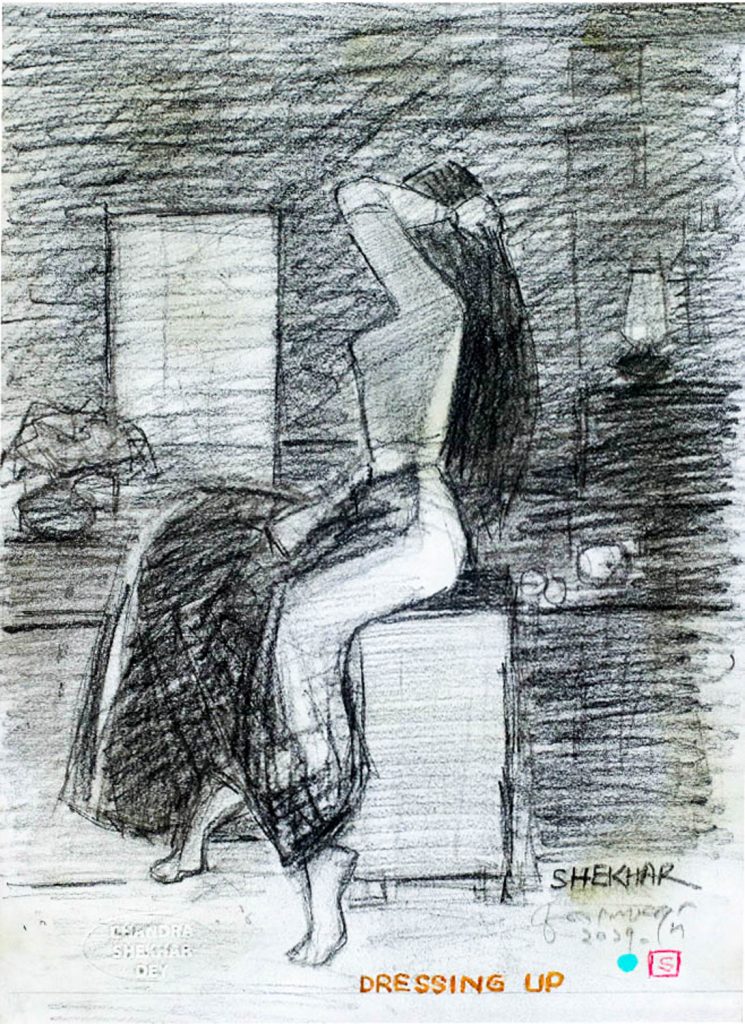

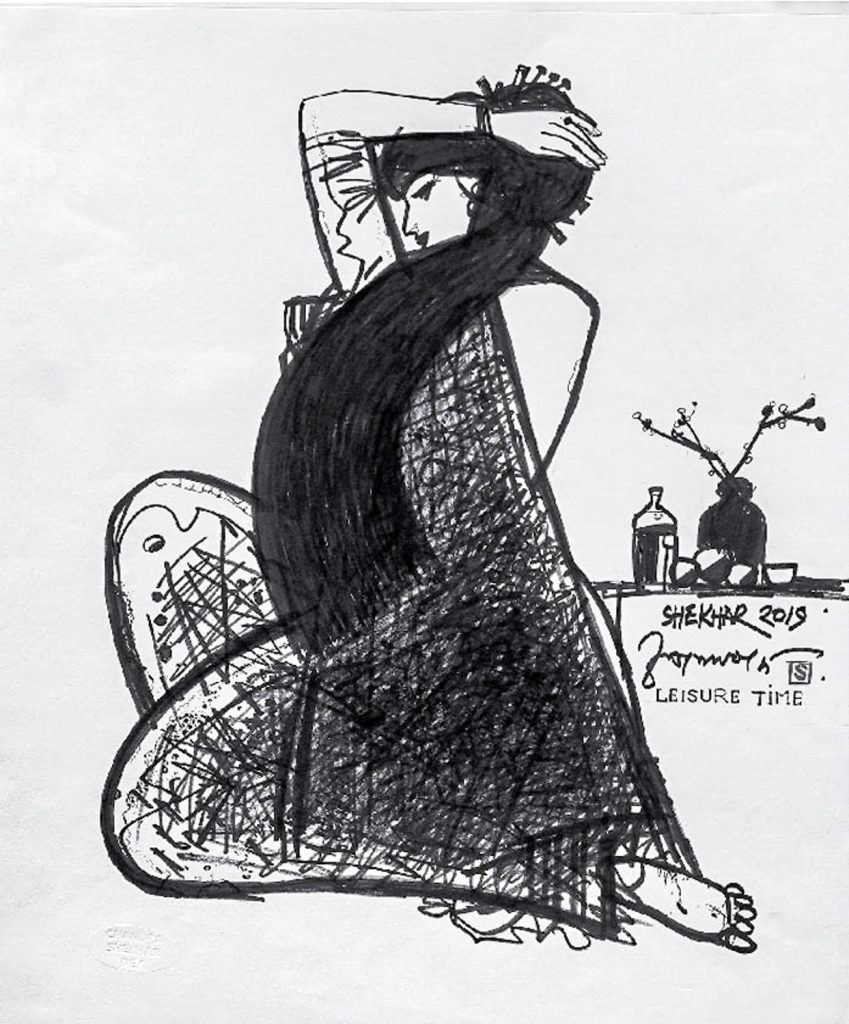

Despite health complications, Dey continues to create art regularly, preferring pen work and drawing for their ease of handling.

“I’ve done work for book covers, illustrations. There was a time when I earned primarily from portraits,”

he shares.

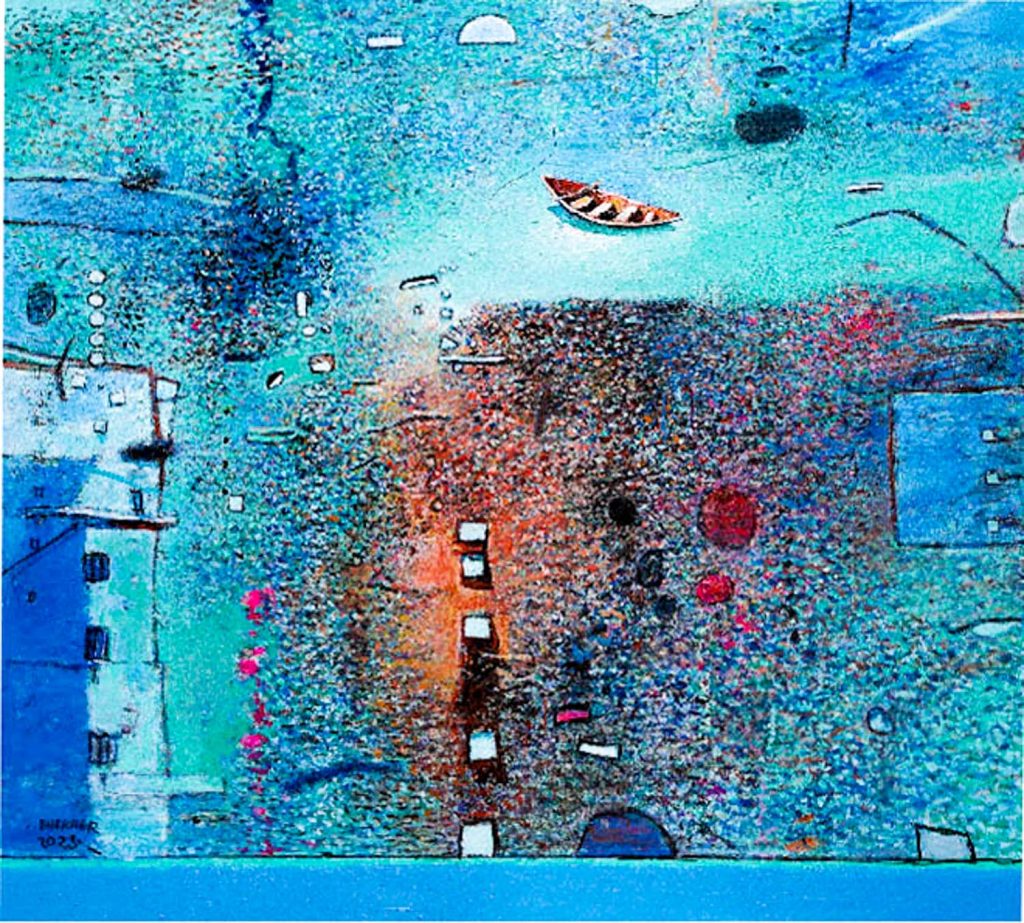

During his extensive travels, he visited numerous art institutions in London, Paris, Moscow, Malaysia, and India. “As an art teacher, I sought to understand different educational systems and observe the evolution of art across centuries and cultures,” states Chandra Shekhar Dey.

One striking observation Dey made during his travels was the discrepancy in the representation of art from different regions in international exhibitions, museums, movies, textbooks, and references. He observed a clear preference for European and American art, while artworks from Asian countries or communist countries were often overlooked.

“There is a clear division. An exception from the Asian countries would be Japan. They keep reusing the same three paintings from Japan, the woodcut block prints,” he notes.

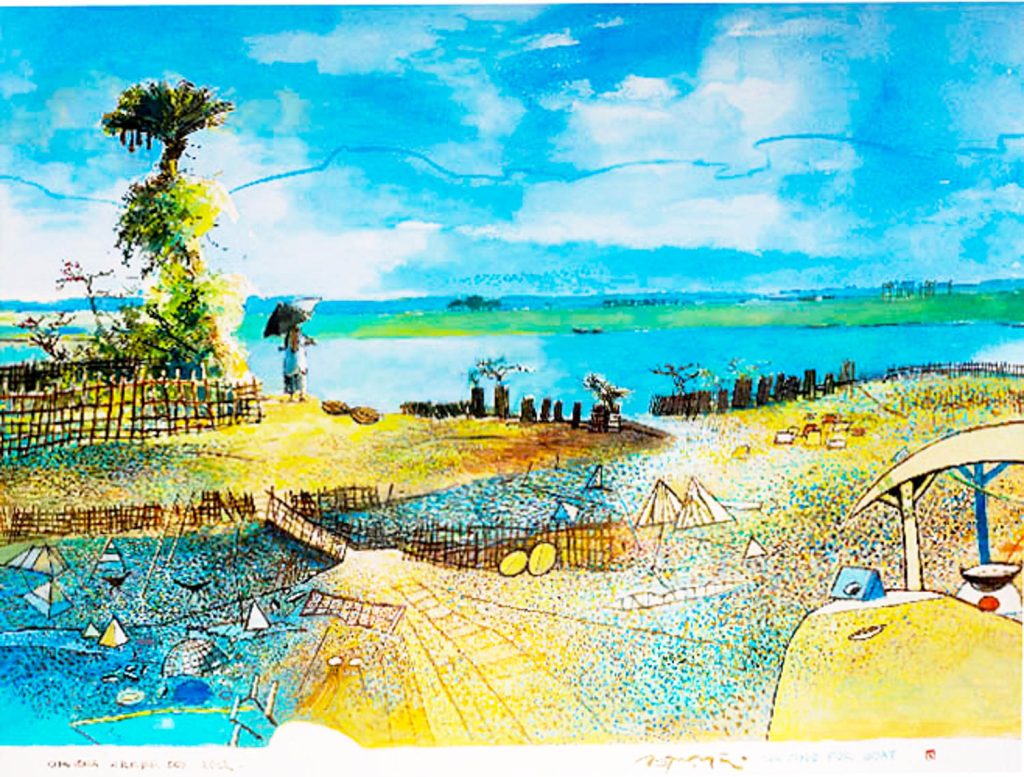

Dey remarked on Bangladesh’s artistic standing, “Bangladesh is on par artistically with the world. They are no less qualified or capable.” However, he highlighted economic disparities, stating, “Countries with better economies, artists there, if they sell 10 pieces, that is enough for them to survive on for a year. In Bangladesh, that is not the case.”

The artist reflecting on the past notes, “It is only in the past 25 years that a market for art developed in the country. After college, I lived in Chittagong for a while, working at a private art college, which is now a part of a university. There was a young man who owned a gallery. He used to visit my home quite regularly; he had heard that I was an artist. I used to sell him my work at a very low price. No one really bought any paintings. People first started buying art in Bangladesh during the industrial boom. But, there were still very few buyers– Sometimes a few foreigners bought a few pieces, that’s it. Artists used to visit government offices to request the officials to help sell their art. There used to be some grants, a maximum of just three thousand.” However, Chandra Shekhar has observed a positive shift in the Bangladeshi art scene.

“Now there are collectors in the country, their mindset is to preserve the masterpieces of Bangladeshi art— they hope, one day when there are museums, they will be exhibited.”

He expresses admiration for the newer generations of artists, saying, “They’re so full of life. They love their craft, they don’t work out of some obligation for survival, but a genuine love and admiration for art.”