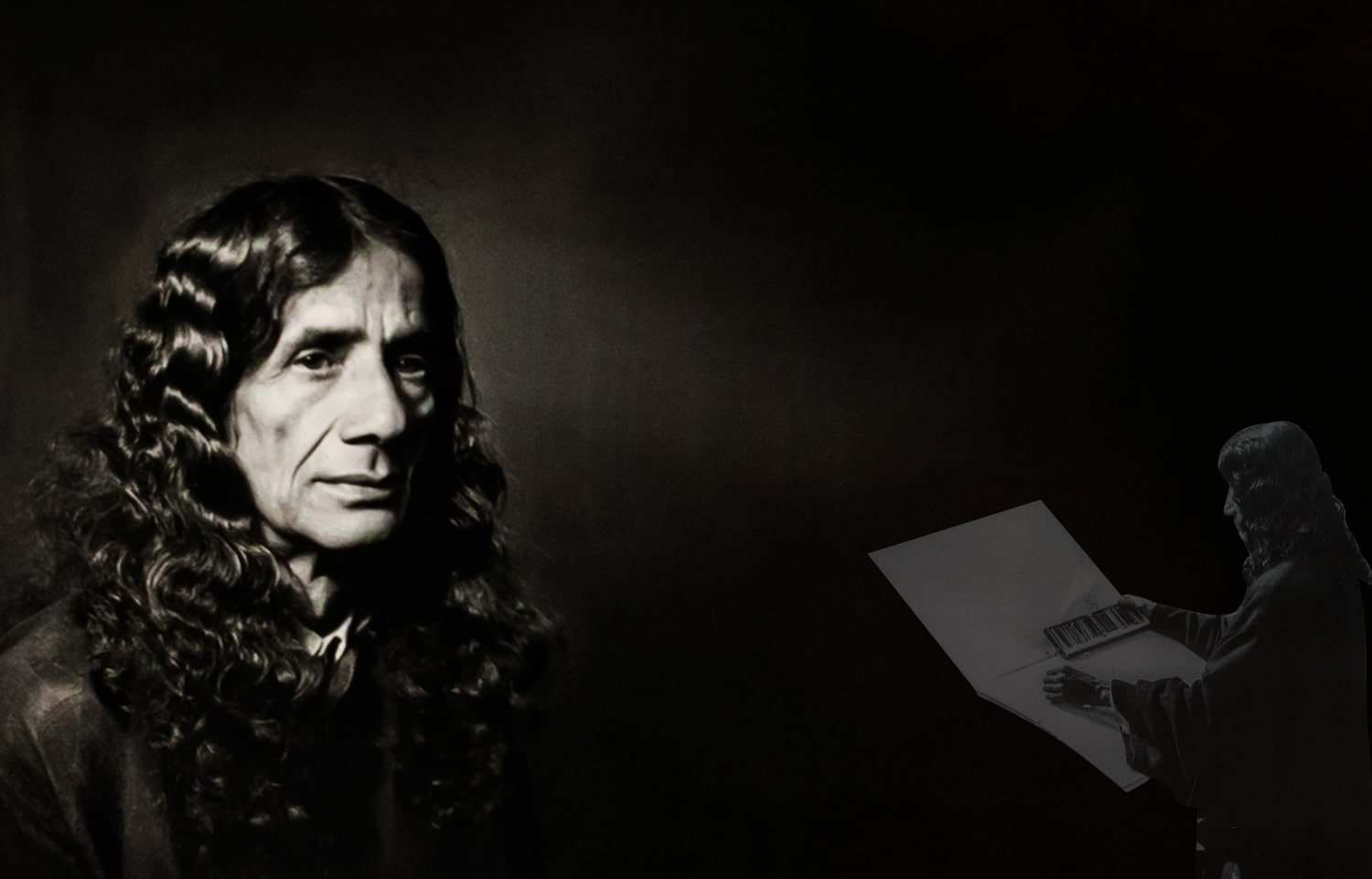

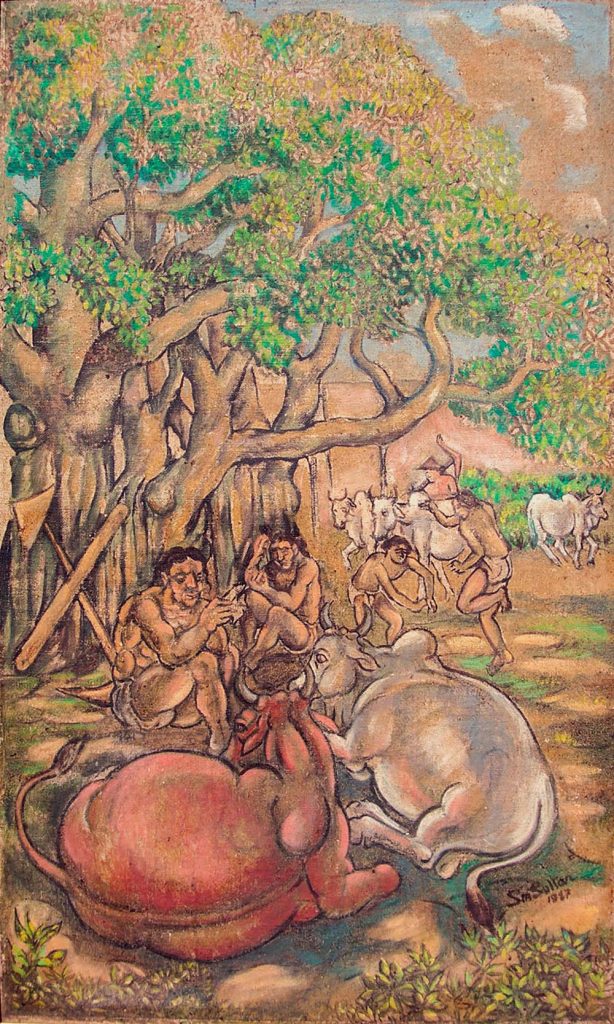

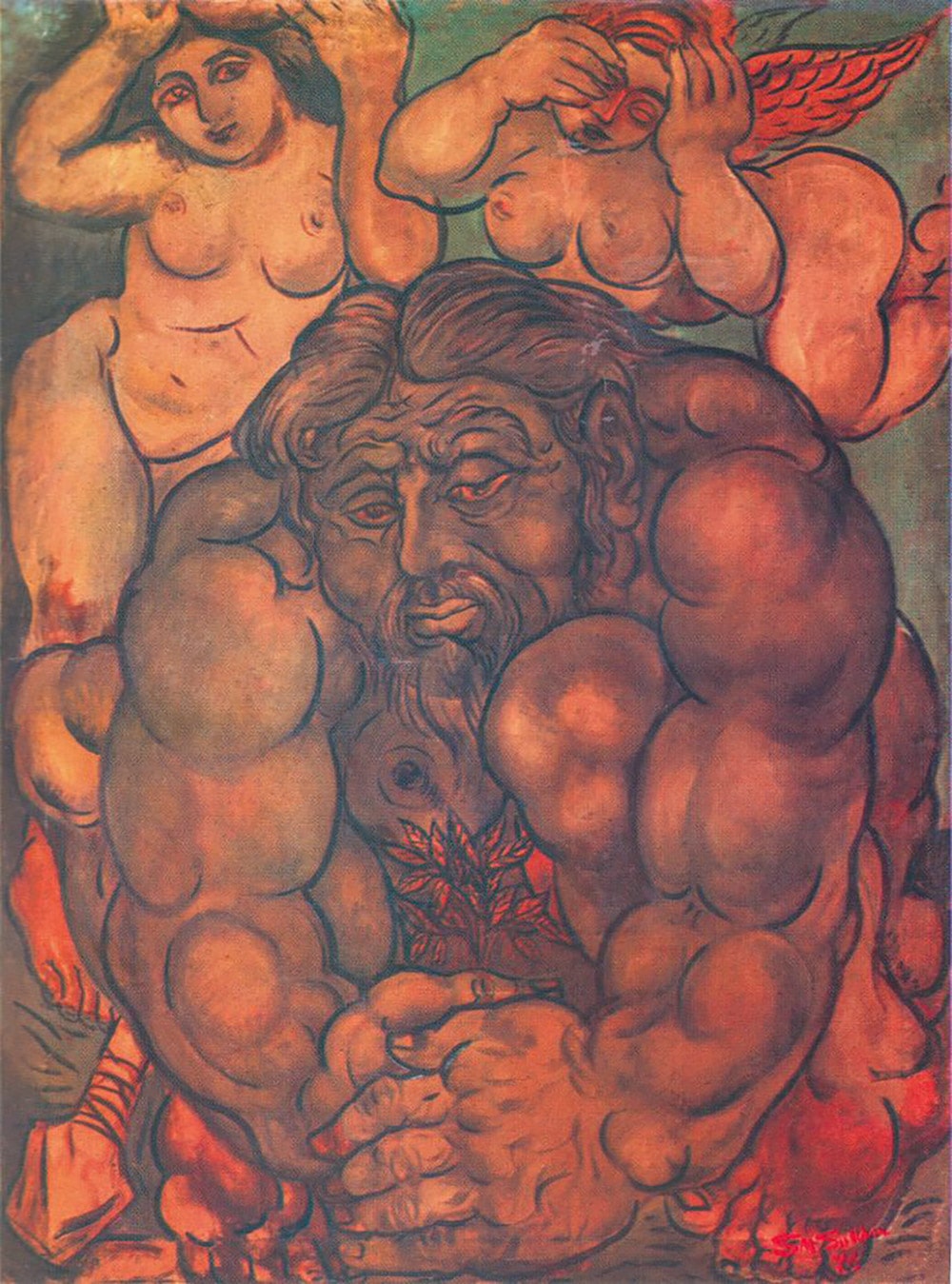

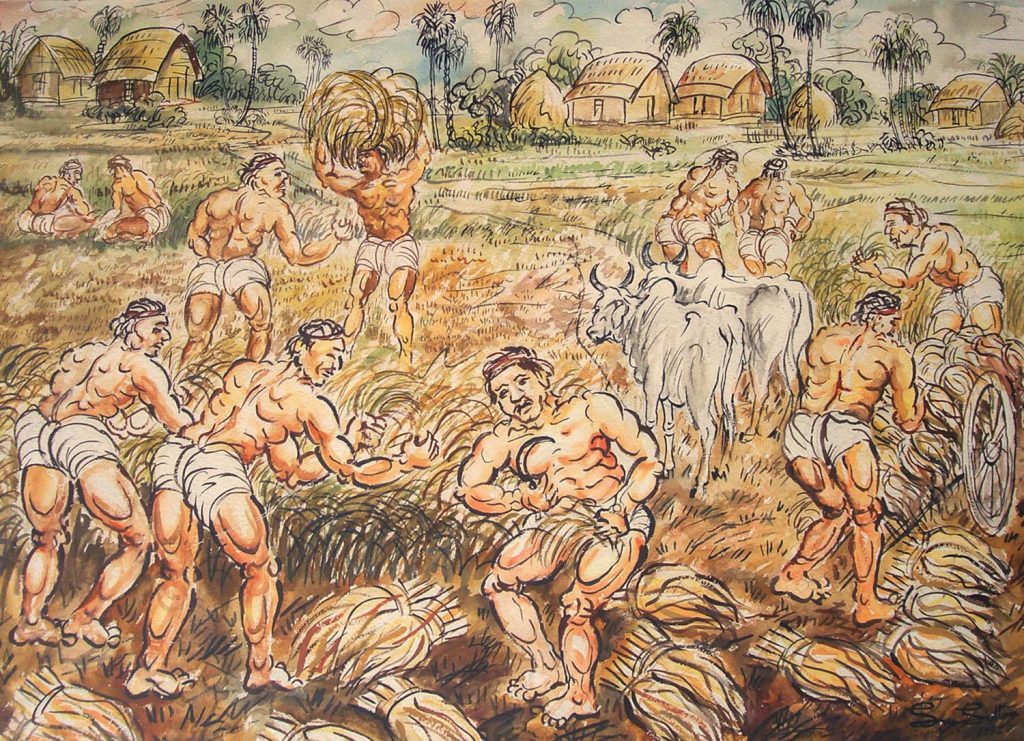

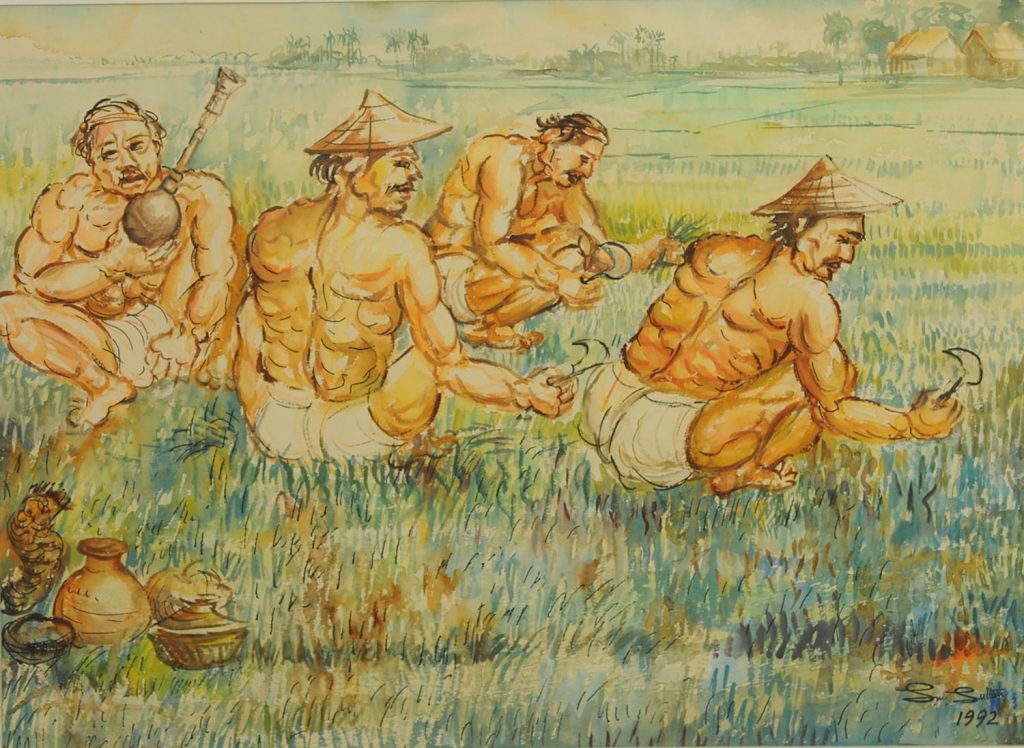

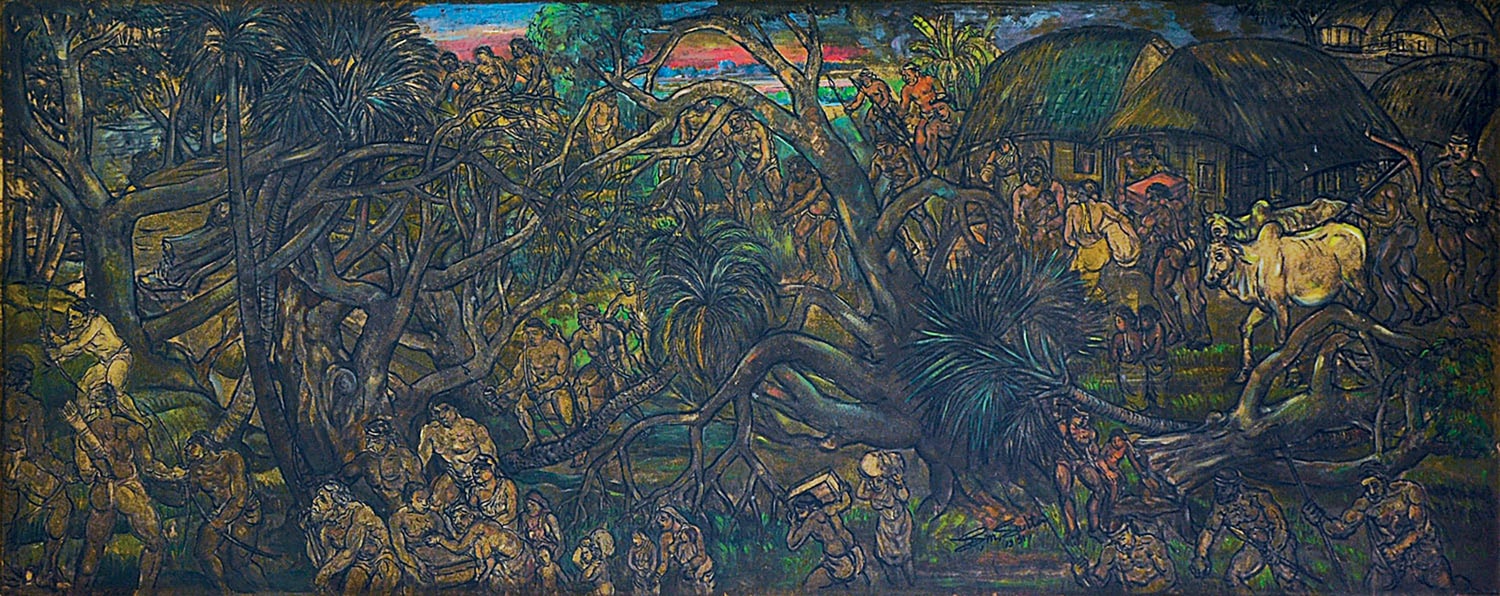

Scrolling through some of the art of the 1971 liberation war, it is hard not to come upon the arts of one of the most influential and non-conforming artists of Bangladesh, Sheik Mohammed Sultan, popularly known as SM Sultan. Shaking the conventional narrative regarding the depiction of the weak and starving bodies of the peasants at the time, Sultan, helming the direction of modern arts in Bangladesh with larger-than-life art, portrayed these farmers, labourers, and fishermen with swollen and exaggerated muscles. These portrayals told a different story, one of inner strength and hard work overcoming the trials and tribulations of poverty and sorrow for the love of soil and joy.

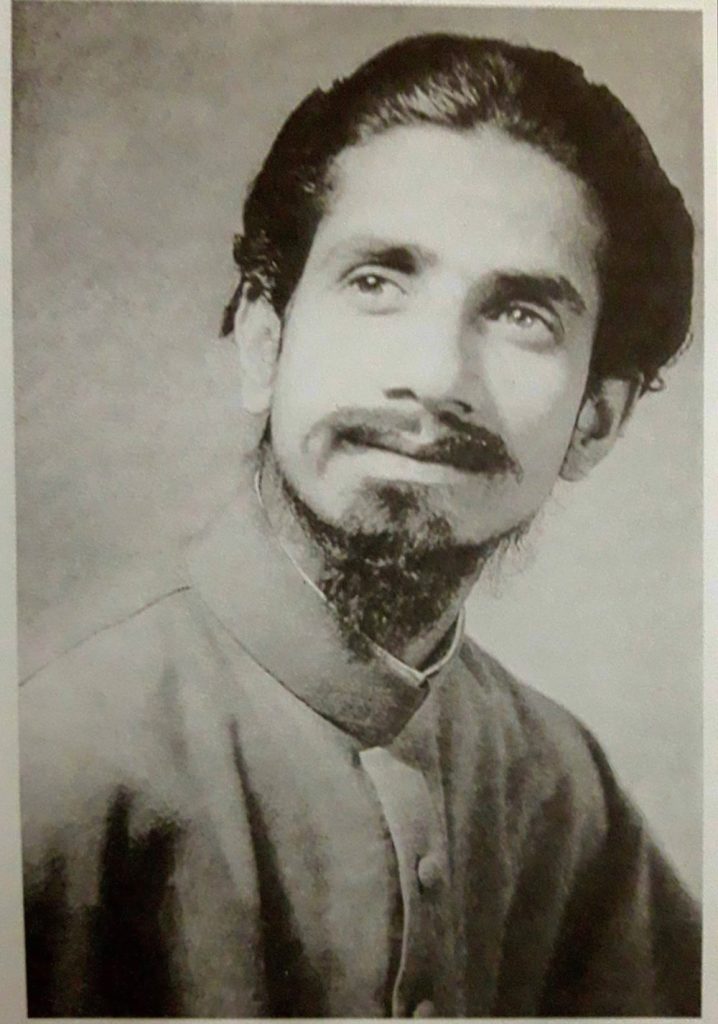

From a very young age, Sultan had a powerful artistic urge and found love in charcoal sketching. Young Sultan was unable to continue formal education due to his family’s poor financial state and started working with his father who was a mason. Back then, Sultan often sketched the buildings his father worked on. Later, with the help of an art-loving local zamindar named Dhirendra Nath Roy, Sultan managed to continue his studies at Narail’s Victoria Collegiate School and later, the zamindar also helped him financially to go to the Government School of Art in Calcutta. Sultan, who did not meet the entry requirements to study at the art school still managed to get in with the help of another patron – Shahed Suhrawardy, who back then was serving as a member of the governing body of the school. Sultan started studying at the Government School of Art in Calcutta in 1941 but halfway through in 1944, Sultan dropped out. However, the learnings from the school – where students were encouraged to paint contemporary landscapes and create original art pieces from their own life experiences – propelled SM Sultan in his lifelong journey with art that revolved around the theme of nature and rural life. After dropping out of school without a degree, Sultan travelled widely across India and Pakistan and made paintings and sketches of landscapes of various places in the region. He had his first solo exhibition in 1946 in India’s Shimla. Later, he had two more exhibitions in Pakistan’s Lahore and Karachi – in 1948 and 1949.

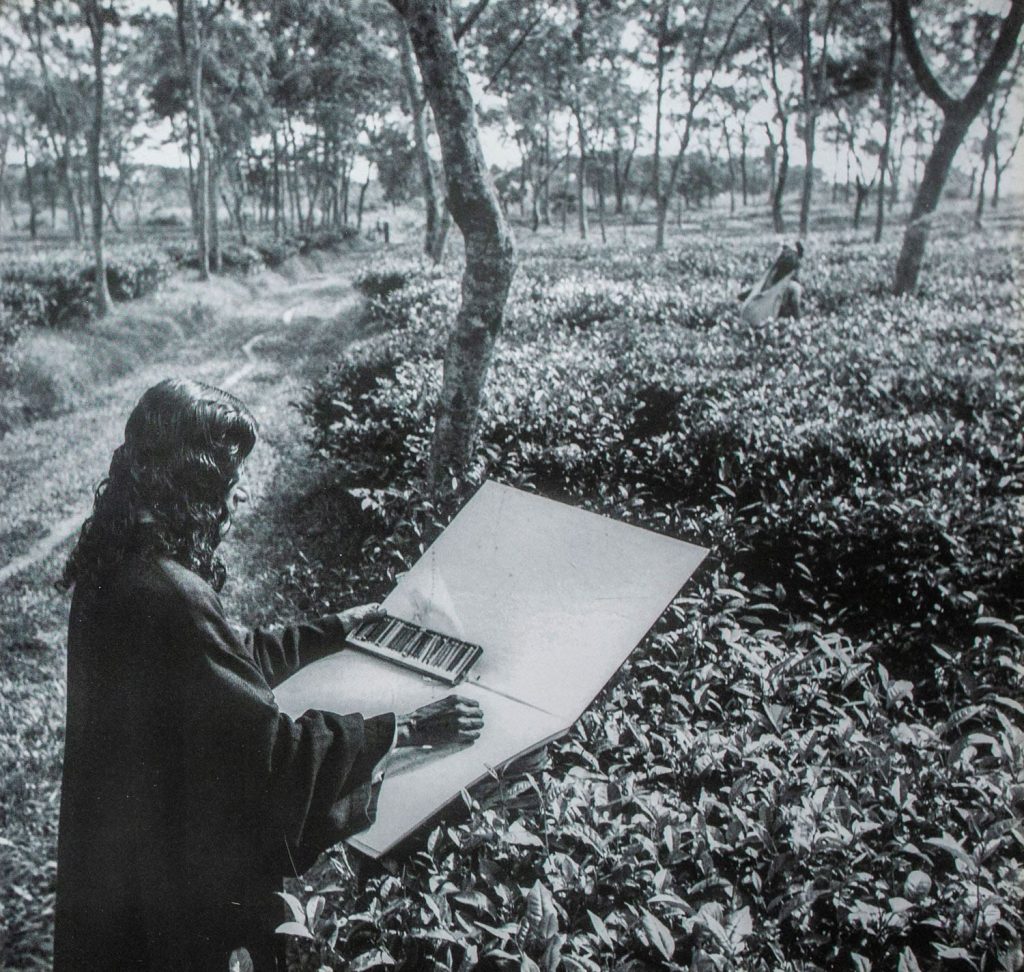

Commencing his art journey with portraits of landscapes taking inspiration from the changing mountains and valleys in his passage through countries and influenced by the distinguished strokes of the impressionists, Sultan displayed his work across his expeditions.

Even though his art took a turn, hints of decolonization of his art style were ubiquitous, his early works were a vessel to his later style.

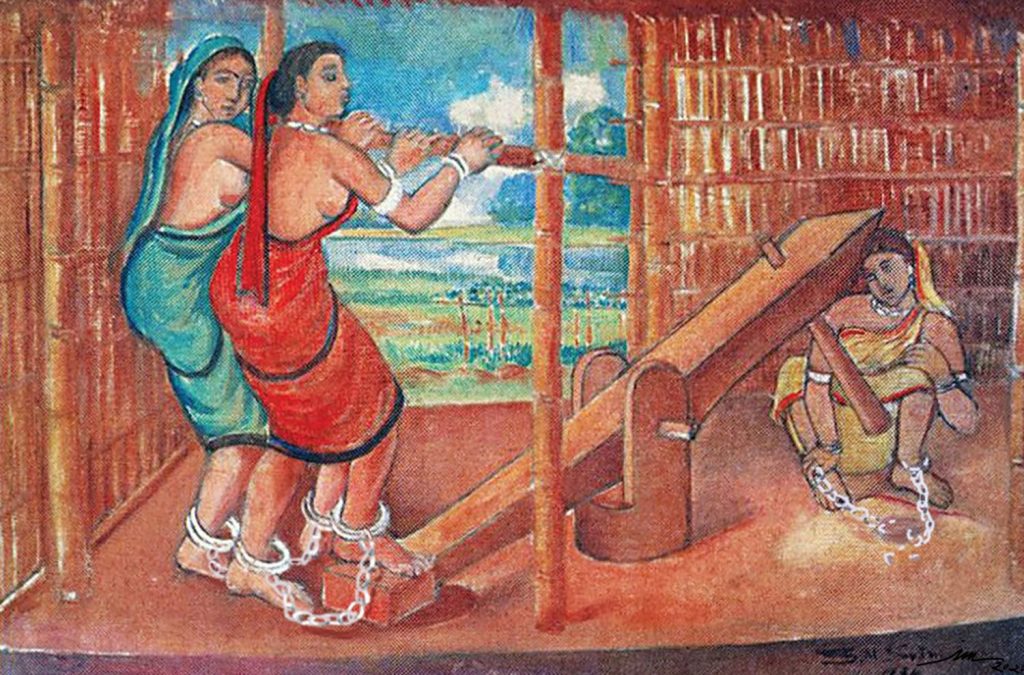

A contrast nonetheless but his understanding of the resplendent impressionism helped him rediscover his love for his country and continue to produce art capturing the normal lives of his people in lush natural environments. One of the novelties of his art among Quamrul Hassan and Zainul Abedin is his representation of working-class rural women.

Muscular just like the rural men and working alongside men in all physical works, it could be said that women were taken out of the conventional framing of patriarchal society and placed in the utopia of feminism.

His art empowers the struggles of our farmers through the physical embodiment of their inner strength and power reflecting their hard labour bringing fertility to this land for thousands of years.

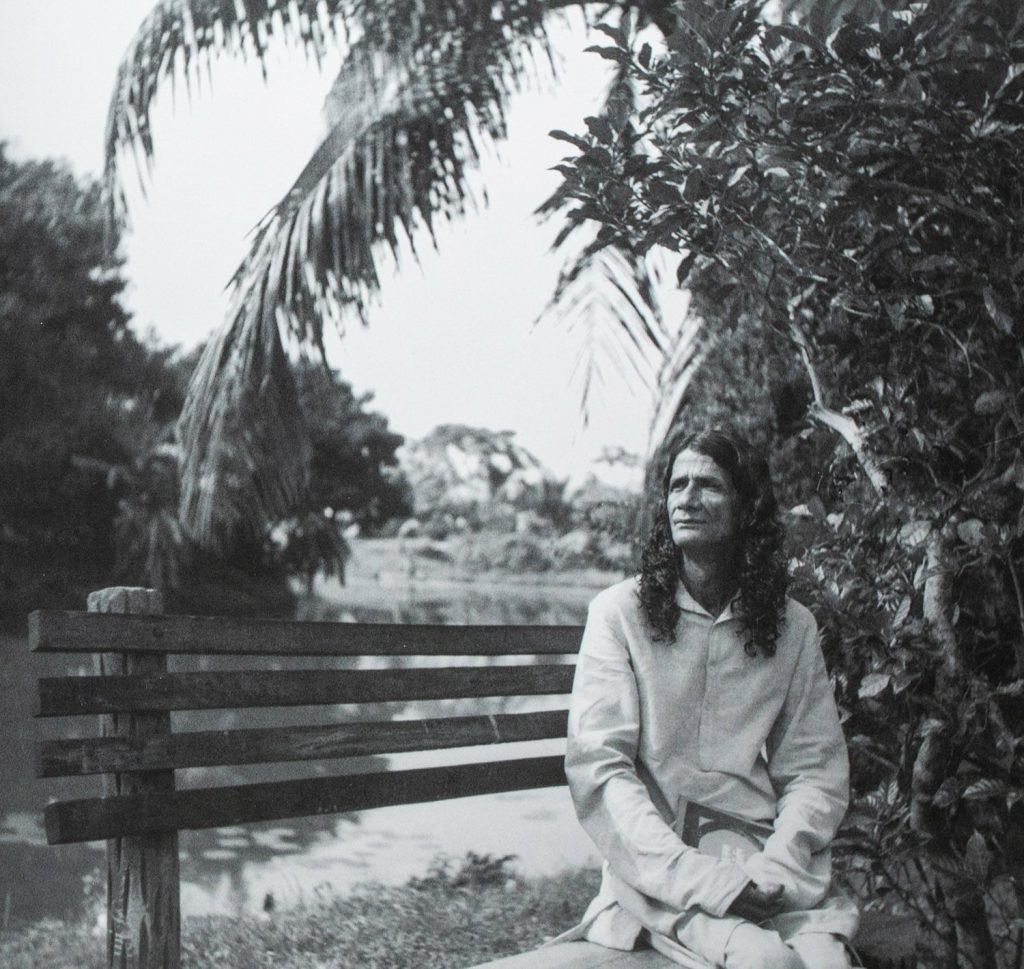

In the early 1950s, Sultan visited the Institute of International Education (IIE) in New York to attend an International Arts Programme where he represented Pakistan. The fully-funded programme allowed Sultan to explore various museums in the United States of America (USA) while getting to know art and artists from around the globe. During his visit, his art was exhibited in New York, Washington, Boston, Chicago, and Michigan. After completing the programme, he visited England to attend London’s annual open-air group exhibition at Victoria Embankment Gardens where his paintings were on display with the works of Picasso, Dali, Braque, Klee and other world-famous painters. After returning, Sultan joined an art school in Karachi as a teacher and in 1953, Sultan came back to his roots in Narail to settle down. He spent the rest of his days in an abandoned house overlooking the River Chitra. Living far from the art world for the rest of his life, he found solace in the company of cats and snakes.

The government of Bangladesh honoured him with Ekushey Padak, the country’s highest civilian award for contribution in the field of arts, in 1982. For his contribution to art, he also received the Independence Award also known as “Swadhinata Padak” in 1993. Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy also introduced the “SM Sultan Gold Medal” to encourage notable artists in the country.