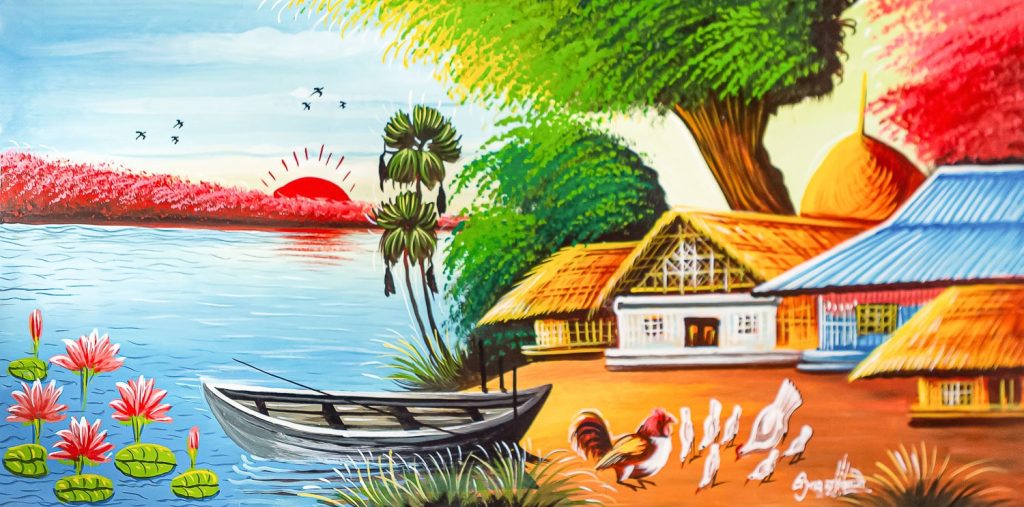

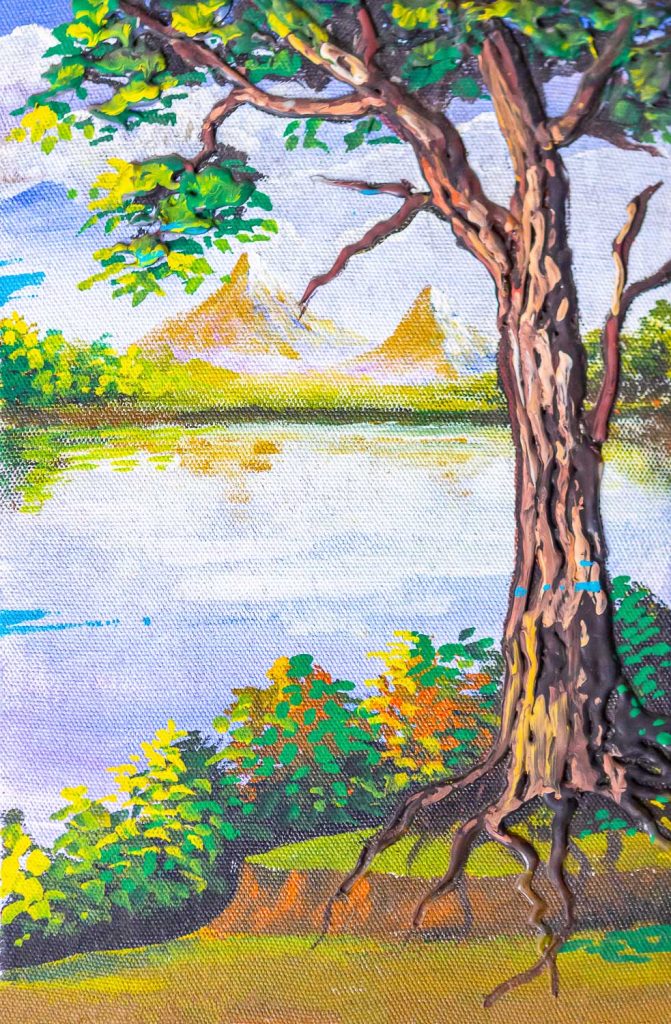

Intrinsically tied to the land even before it became Bangladesh, rickshaw art holds a special place of heritage on our artistic stage. Before it became rickshaw art, the artform traces its origins to film banners. Artist Mohammad Hanif Pappu’s journey throughout the boom, fall and rejuvenation of this artform is a story that trails his entire lifetime.

Born in Nawabpur, his fascination with art started at a young age. Hanif Pappu states, “I walked into the profession holding my mama’s hand. I was dropping off food for him when I was a child, and I saw these vibrant shades of red, orange. I haven’t looked back since.” The film banner artist started painting in 1968, seeing the gradual decline in demand when digital banners were introduced. Pappu notes, “When digital banners were introduced in the 2000’s, they were quite expensive, around 500 to 600 taka per sqft. As the banners started to gradually lose the high price tag, we film banner artists started to lose work. It got to a point where digital banners were used 90 percent of the time. We used to have around 12 workshops. We could no longer afford to employ our artisans, pay the rent. One by one our workshops closed down. Because I had my own space, I scraped by until 2005. After that, the whole line became extinct.”

Struggling to survive, Hanif Pappu was forced to scale down his operations, seeking alternatives to put food on his plate. “I began painting for gaye holuds. I painted the wife and husband, making the father in-law or mother in-law the ‘villain’ of the poster. The public was enjoying it, they were consuming it. They called it rickshaw art, but I was just happy to make ends meet. I did not care whether they called it rickshaw art or film banner art.” The veteran artist also painted antique hurricanes, tea kettles, sunglasses and so forth, continuing this practice for nearly 10 years. After coming back to Dhaka post participating in a Denmark based film banner art exhibition 2013, Hanif Pappu set up shop. Expressing his renewed motivations Pappu states,

“Film banner art, rickshaw art, whatever people may call it. I wanted to see if I could salvage this dying art form. I believe that this artform is surviving through me, nowadays I see other artists of this line working towards this dying art form.”

Foreign buyers often commission his work. He recently created two film banners, Beder Meye Josna and Rangbaaz 20ft by 10ft, which were sent to Germany. Hanif Pappu revealed that the Rickshaw Art Association is planning on opening a school focused on teaching people of all ages the intricacies linked to the artform, very soon.

The artist expressed disappointment at many rickshaw art workshops being conducted that have failed to include the original rickshaw artists, “They used to include us in these workshops, but for the past few years that has stopped. I’ve heard of a film banner art, rickshaw art department to be opened in Charukola, however it is disheartening that no veteran rickshaw artists are associated with this project. While undoubtedly capable in their own craft, rickshaw art in its purest forms has elements that only masters of the craft hold the capacity to pass down to the younger generations.”

It is Hanif Pappu’s inherent belief that this practice will slowly dilute this art form, creating misdirections in newer practising artists, while simultaneously taking work away from already struggling artists trying to resuscitate this cultural heritage. It is Pappu’s fervent belief that government or NGO intervention is essential in order to secure the future of rickshaw art. He additionally noted his faith in the growth potential in the artistic sectors, that it is a matter of opportunity and facilities for artists to prosper, stating, “It is an unfortunate reality that people who are already privileged have more of a possibility to grow and sustain themselves through the artistic profession, hence why government intervention is indispensable.”