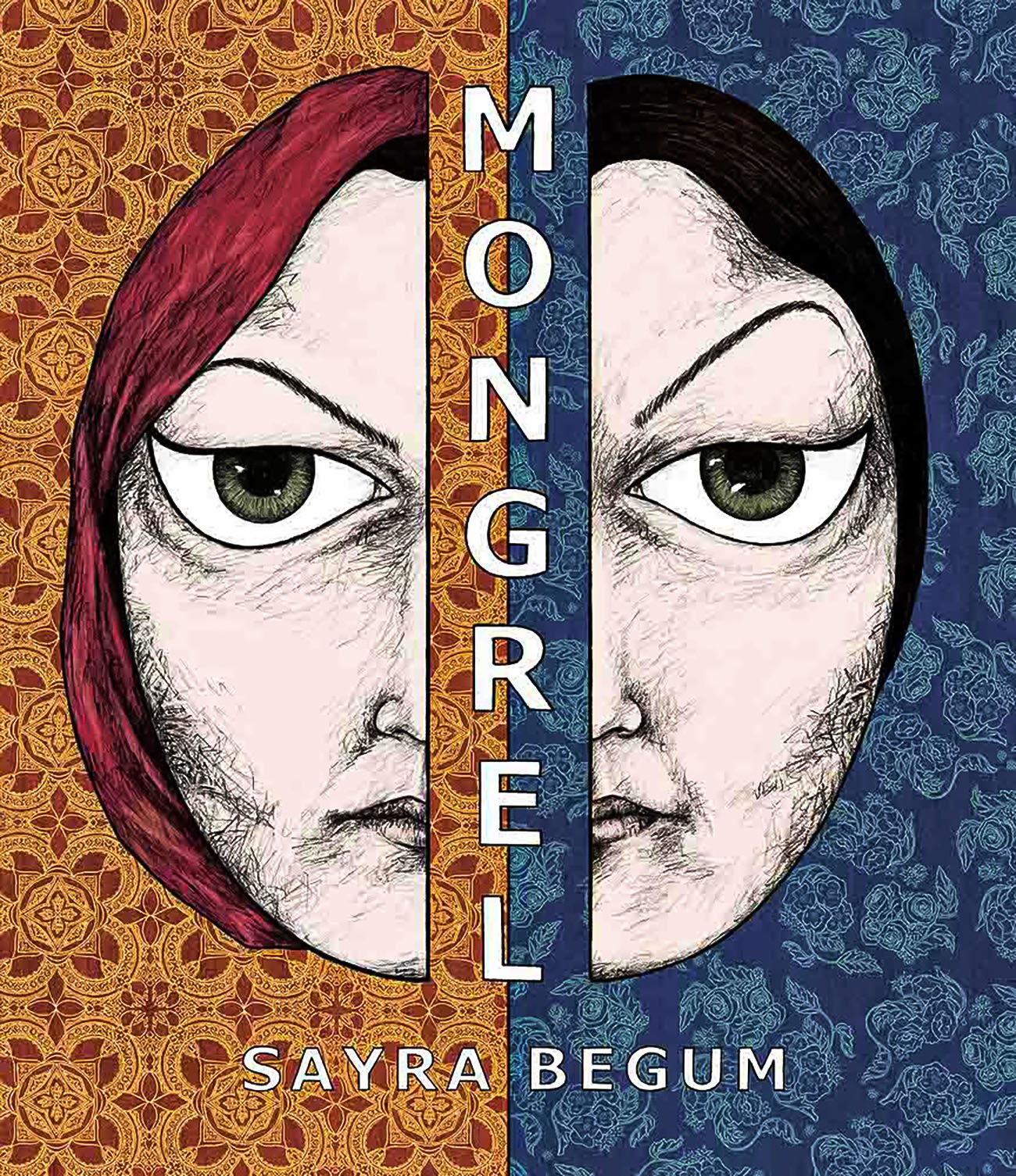

A Graphic Memoir

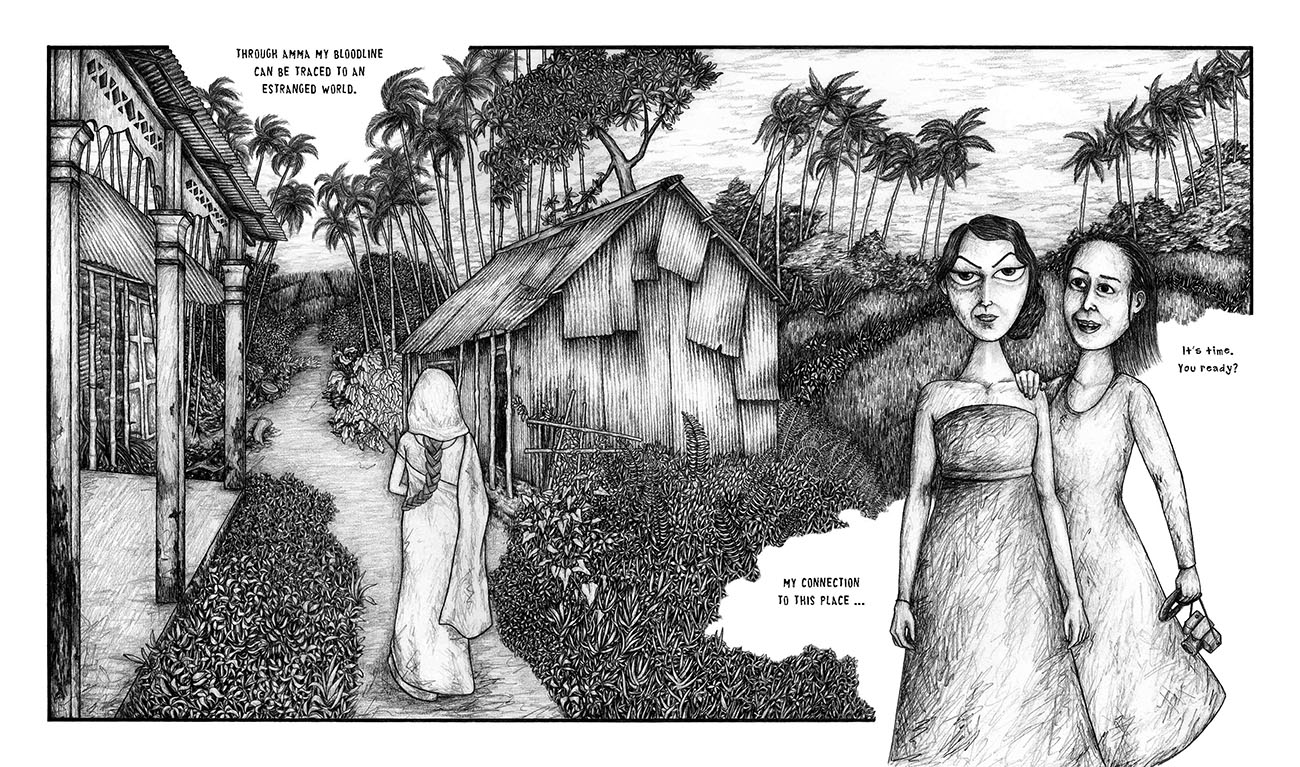

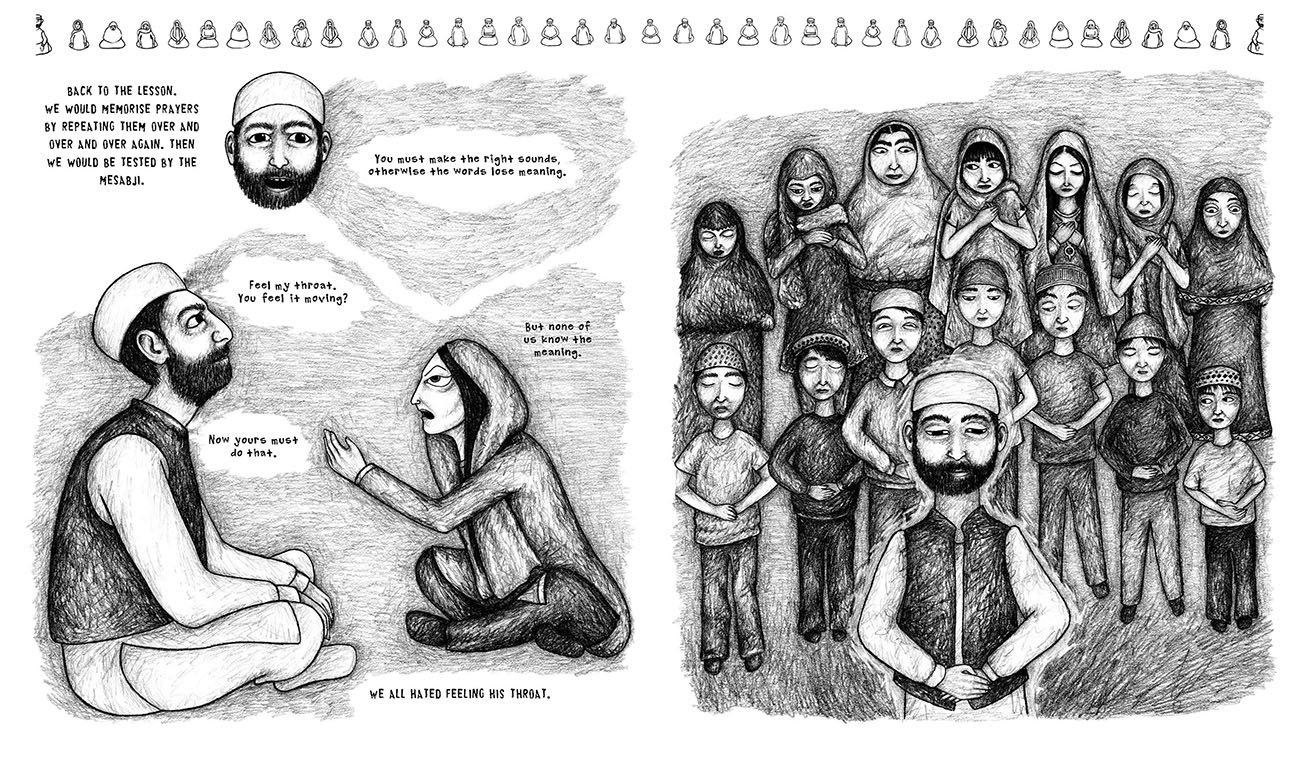

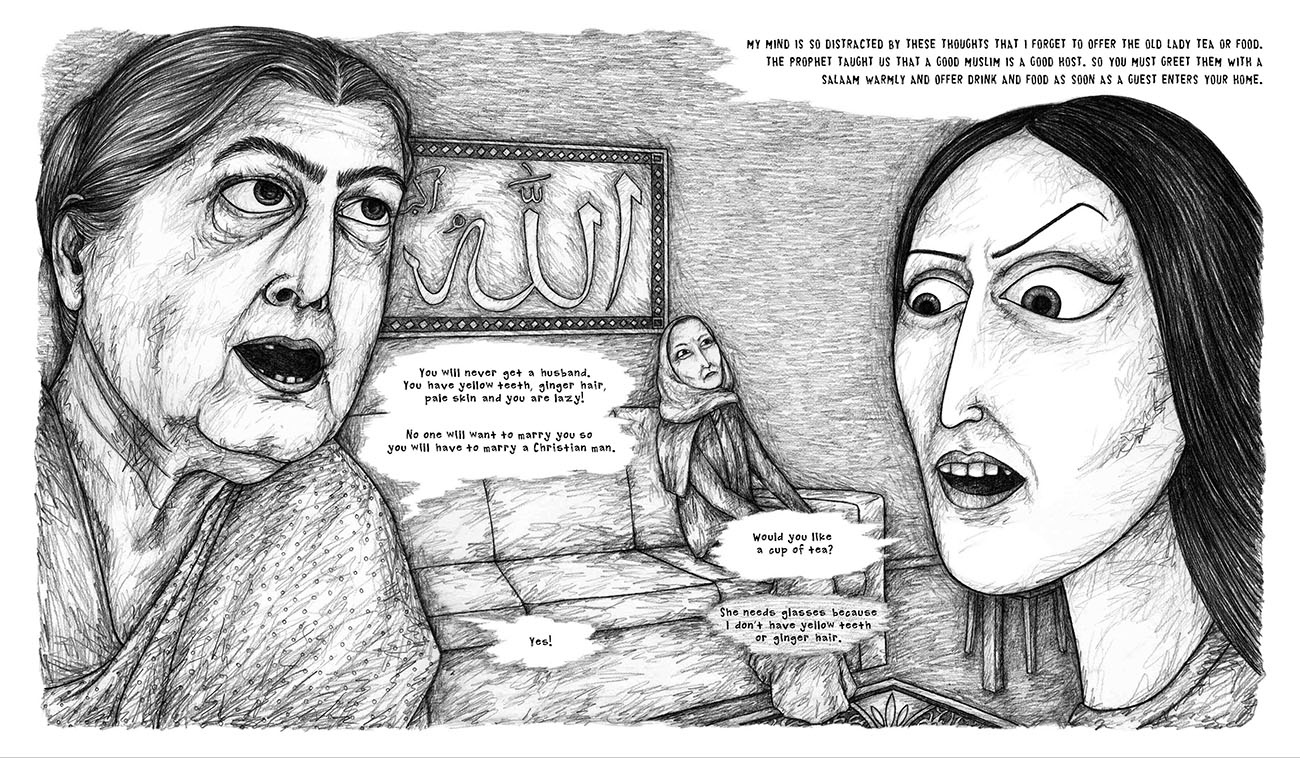

Sayra Begum’s autobiographical graphic novel Mongrel was recently published by Knockabout Comics that illustrates the tale of Shuna, a young British Muslim girl torn between the pull of two cultures. Addressing the typical issues like immigration, racism, intergenerational conflicts etc, the novel makes for an insightful and ambitious debut. Sayra gets candid with Showcase Magazine about her story and inspiration.

Please tell us in brief about your background

I studied BA Illustration at Plymouth College of Art and MA Illustration: Authorial Practice at Falmouth University. Since graduating from Falmouth in 2016, Mongrel has been at the centre of my creative practice until its completion in early 2020 and it’s my first published work.

Your graphic novel ‘Mongrel’ was recently published by Knockabout Comics. What was your inspiration behind this particular work? Does it reflect your personal experience?

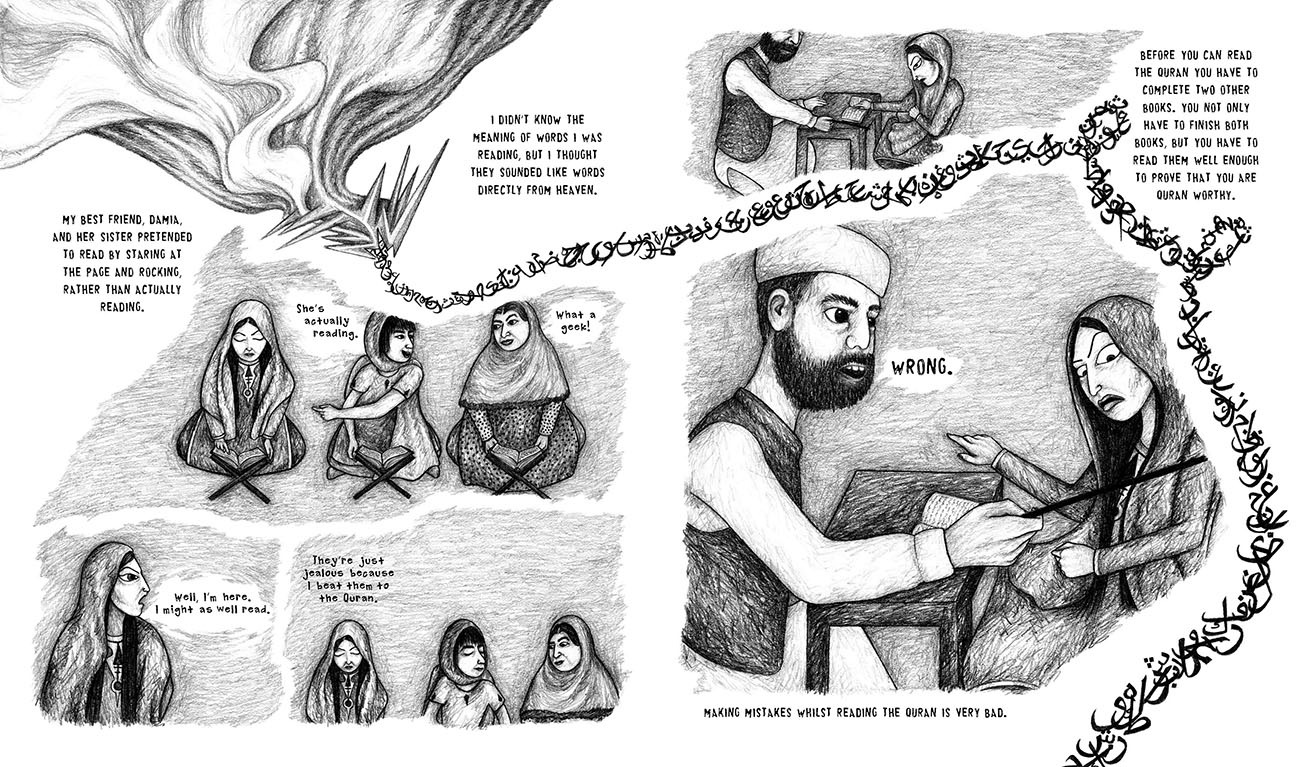

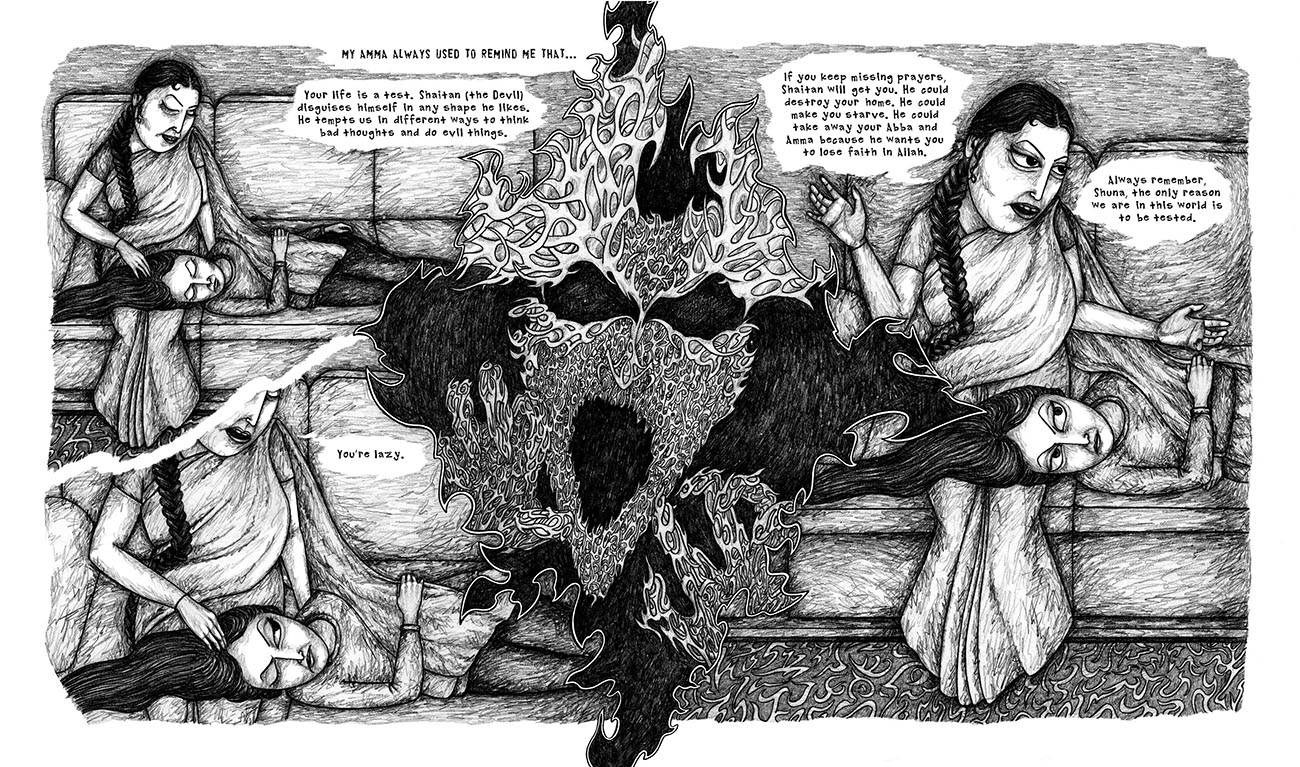

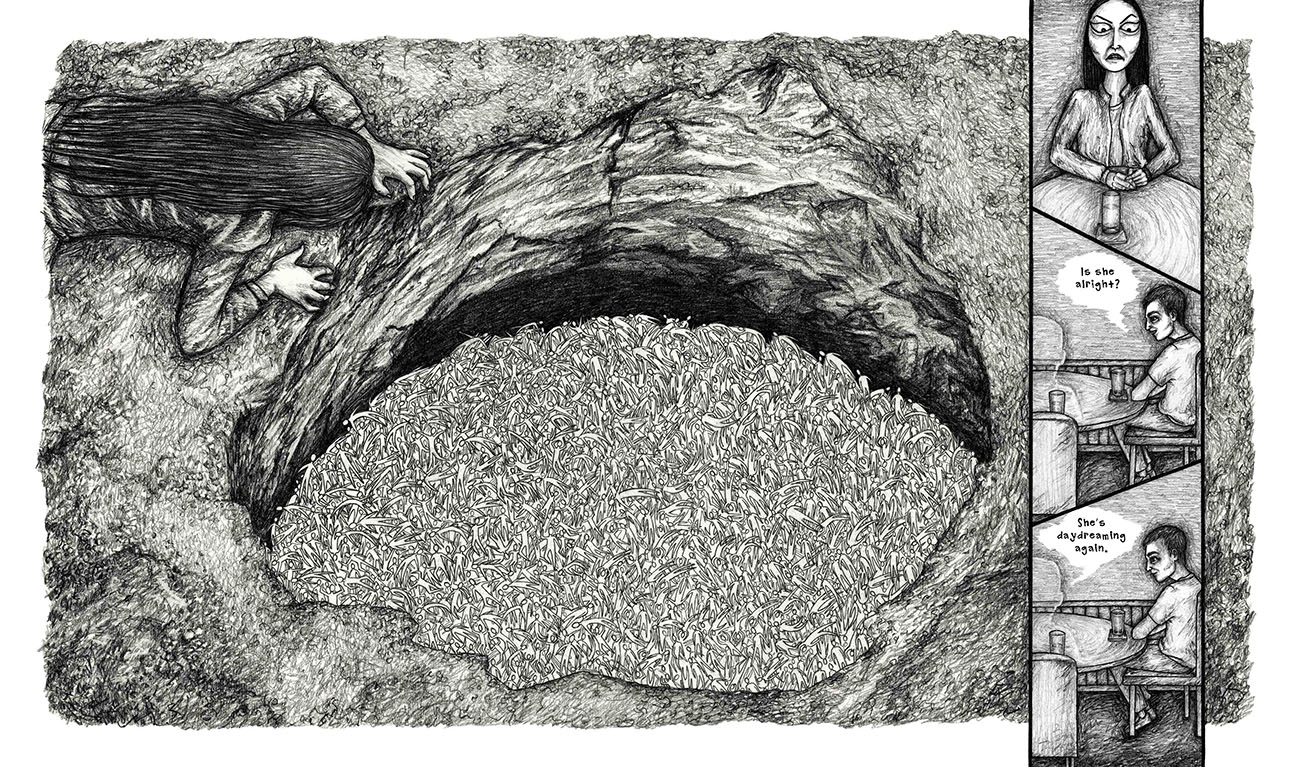

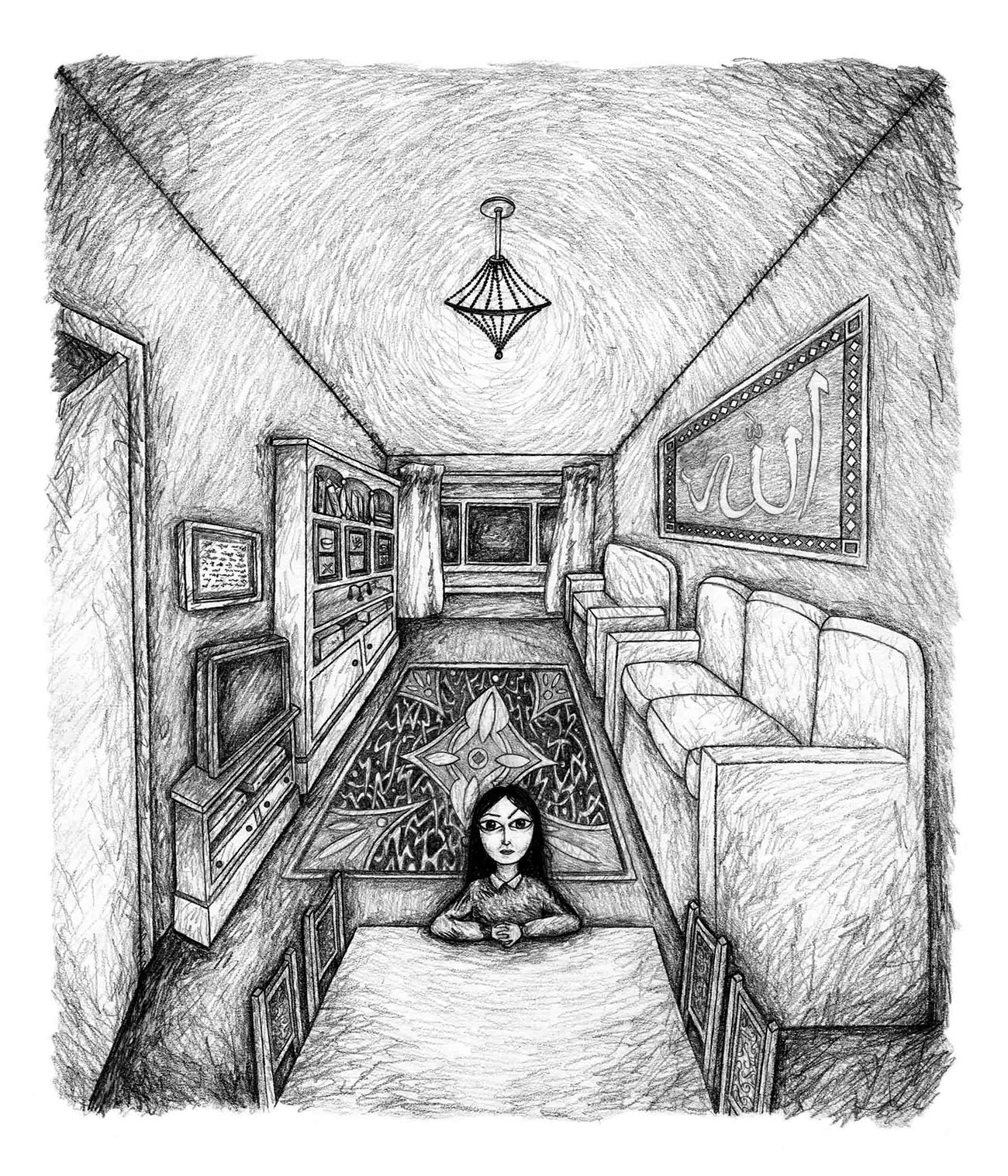

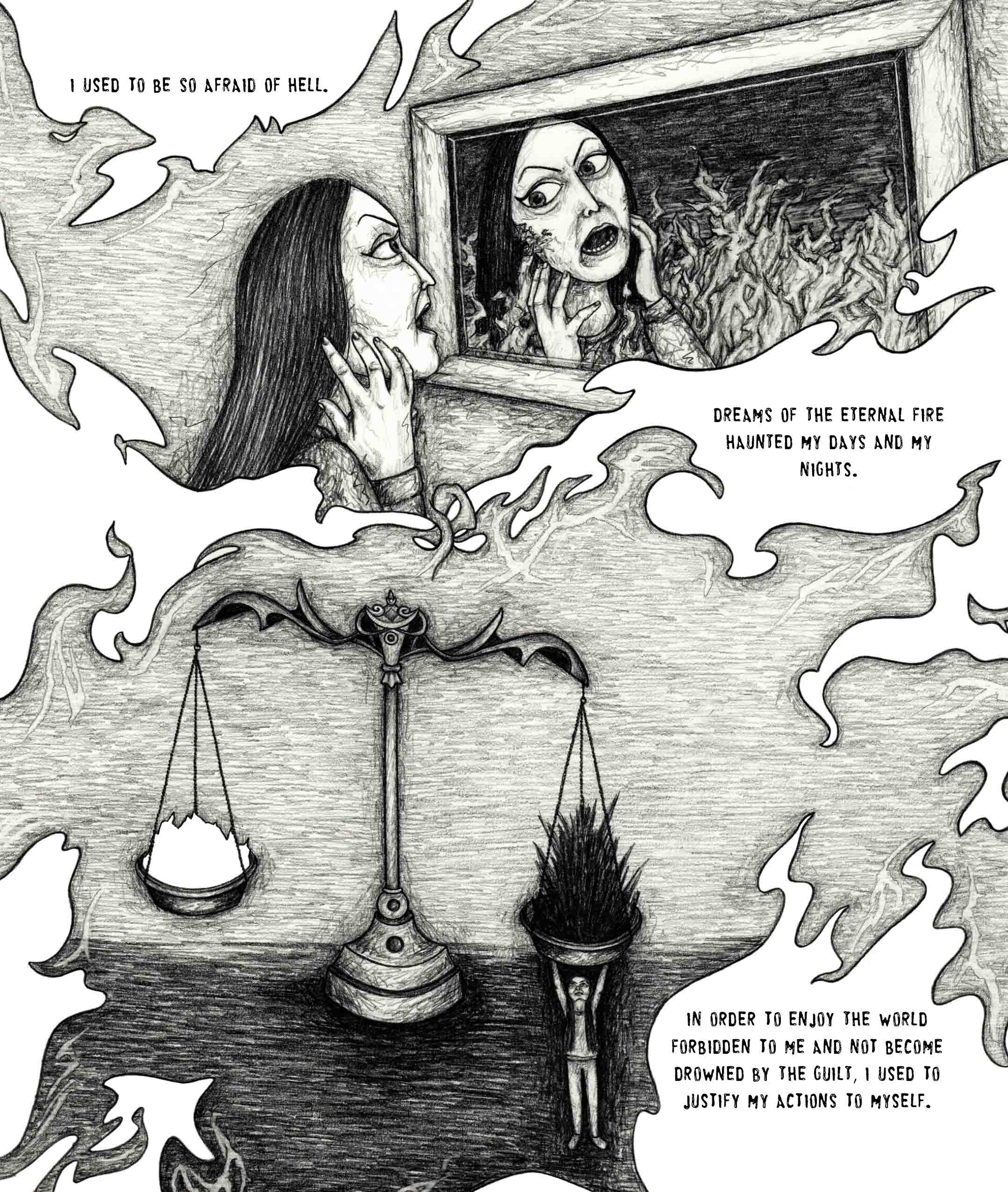

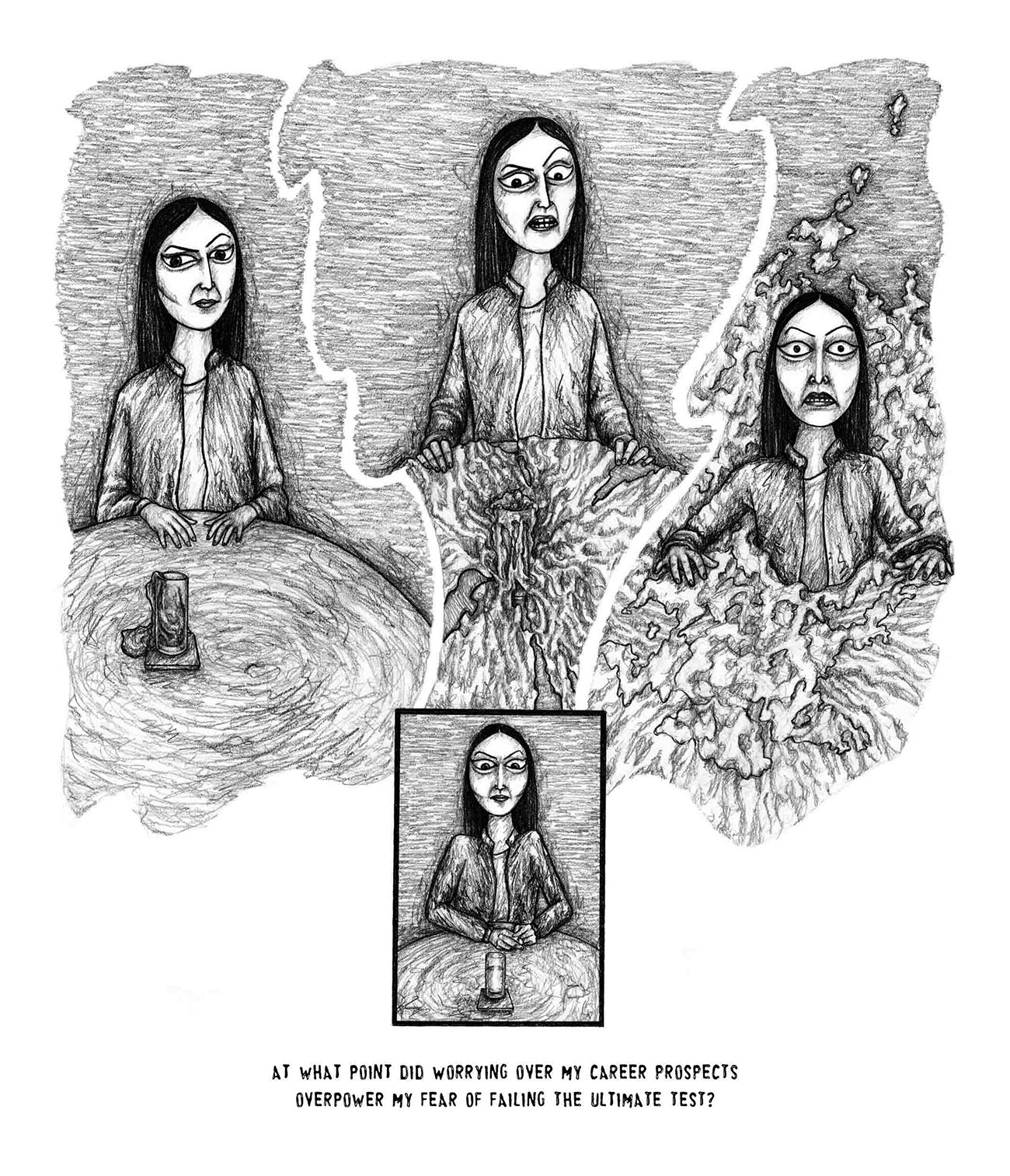

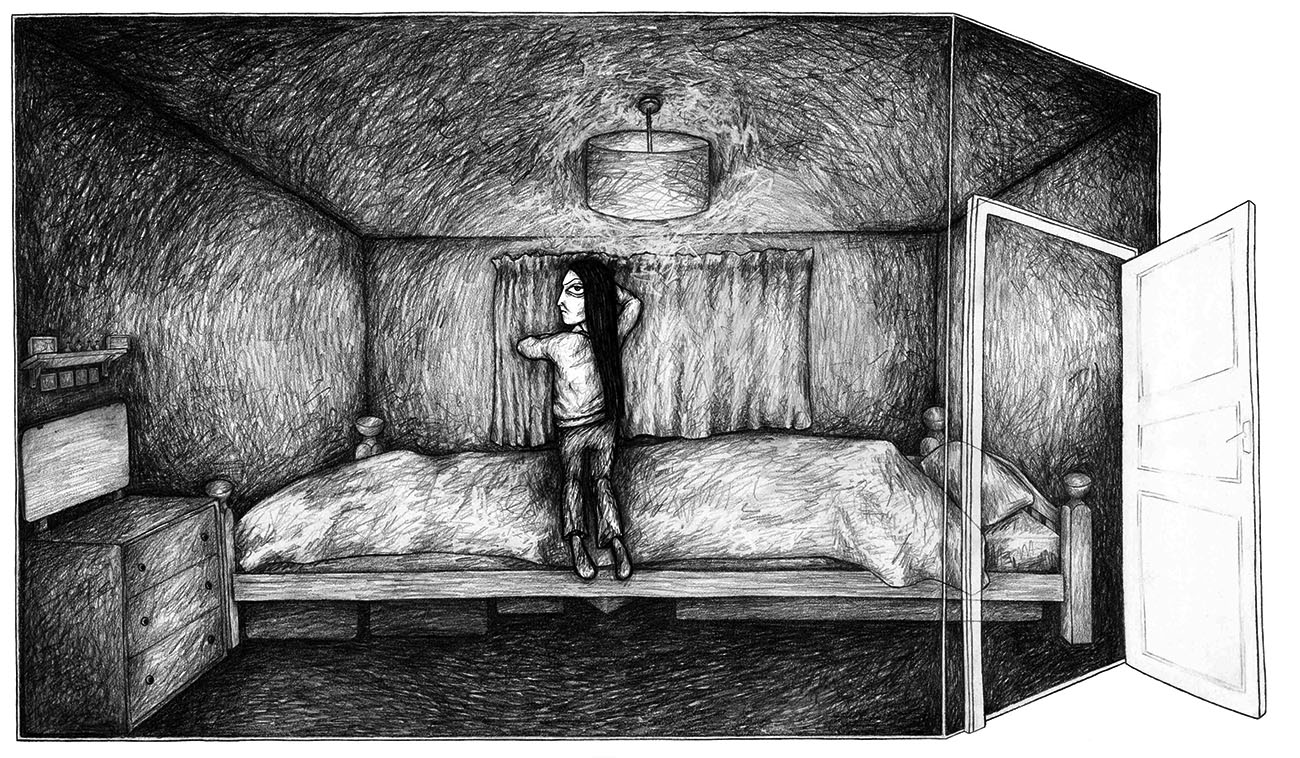

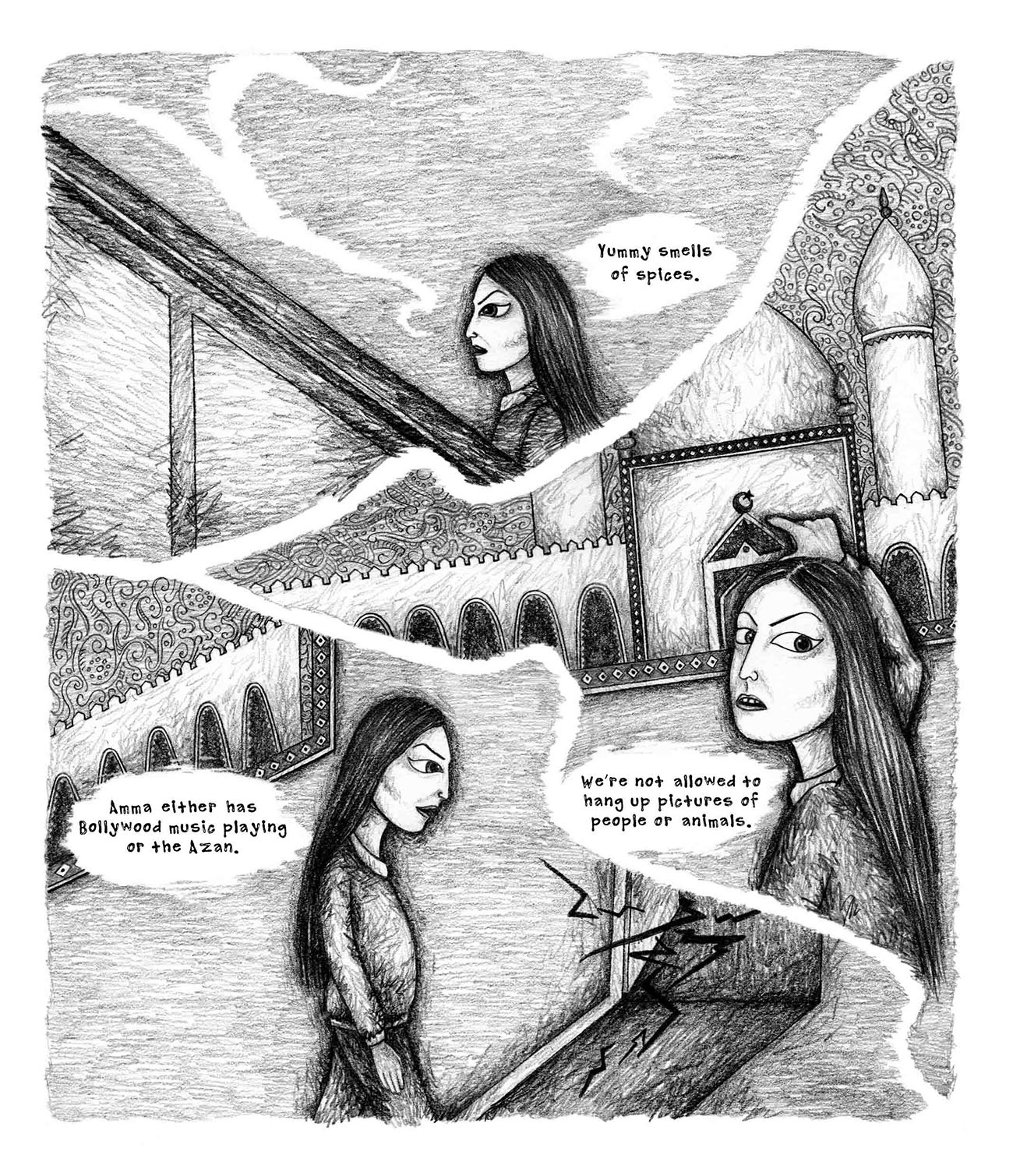

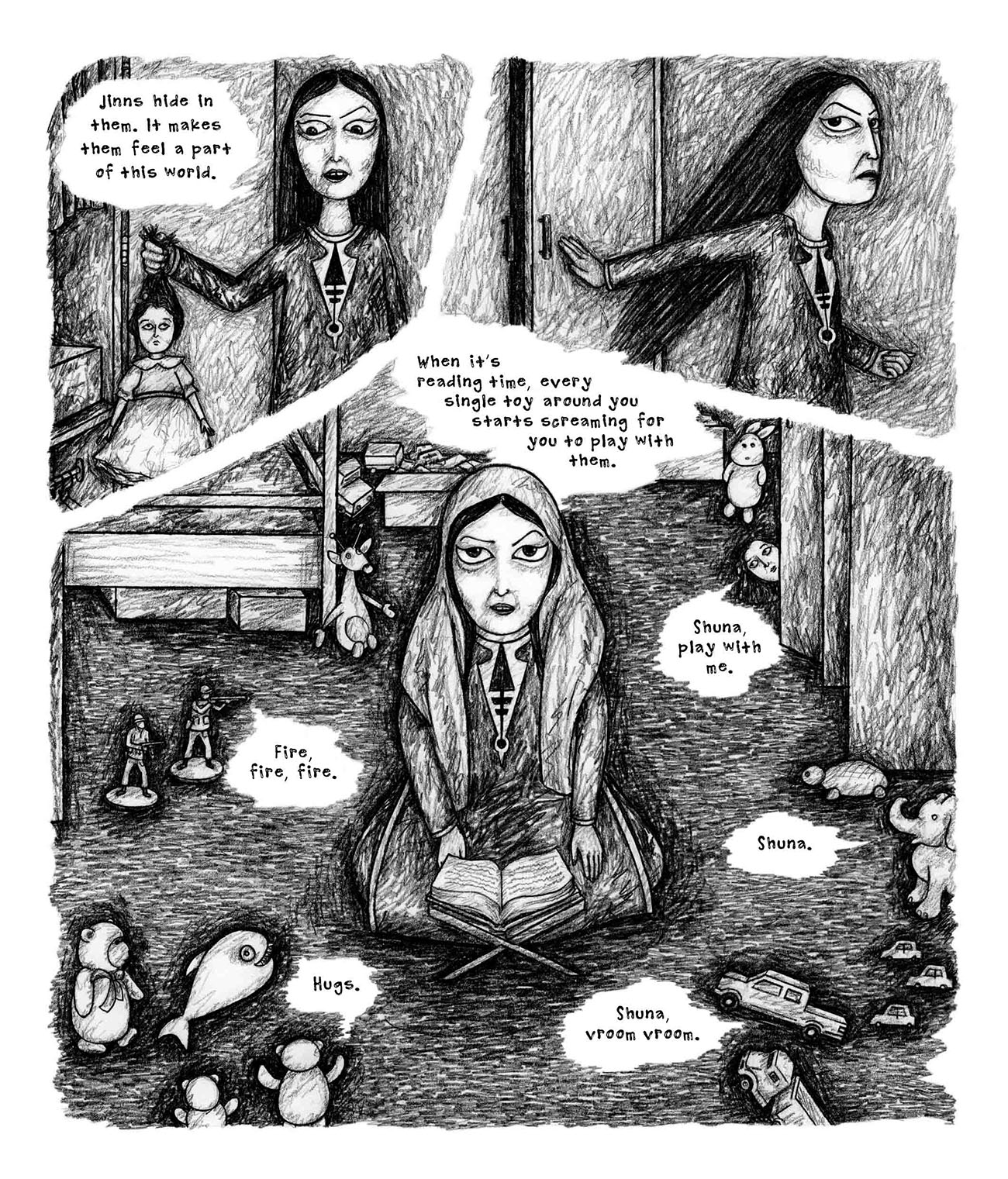

Mongrel is autobiographical and I have tried to stay true to my memories whilst incorporating surreal aspects, perhaps this reflects my tendency to daydream. I think the creation of Mongrel for me was inevitable. In previous work, I would create the most fantastical imagery I could to escape reality, but personal narrative eventually started seeping through into the narrative. When I discovered graphic memoirs in the Plymouth library, this had a profound effect on me. I was building the courage to allow my work to be personal and started seeing the benefits of doing so.

I could use my story, my in-betweenness, as a bridge for people to explore what they consider to be the ‘other’.

When did you first start working with graphic novels? Why did you pick this particular medium of art expression?

It was in 2014, I started writing a graphic novel based on my grandfather and the story of his possession by a Djinn. This is a story I will revisit.

What struck me about graphic novels was its hybrid nature which appointed equal importance to text and imagery, one unable to exist without the other, unlike picture books where these elements don’t seem so intertwined. The structure of graphic novels enables so many layers of communication from creator to reader, for instance, the pacing of the story using panels and speech, the visibility of thoughts, and multiple timelines and perspective presented simultaneously. Graphic novels rely heavily on reader participation, we have to use our imagination to bridge what we don’t see in the gutter (gap) between panels and readers control time as they can move forwards and backwards on the page, observing again what they have missed and anticipating what is to come.

I think graphic literature is so powerful in how it can transport readers through the simultaneous showing and telling of a story, whilst communicating with the reader on many different levels.

Which graphic novels or artists would you say inspired you the most?

When I first discovered graphic novels, it was Craig Thompson’s Blankets and Habibi and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis which opened this whole new world of potential in my art. I saw how intimate the medium could be, authors are recreating their world on paper and asking you to step inside it, to see through their eyes. My reading became dedicated to those who had chosen to share their memories, sometimes traumatic, uncomfortable or the everyday. Just to list off a few, this includes Aline Kominsky-Crumb, Phoebe Gloeckner and Lynda Barry.

Other than graphic novels, what inspires your work?

I am inspired by Surrealism and Islamic miniatures. In surrealist paintings, for me, there is a state of transformation and this always reminds me how ephemeral our existence and this world is. In my sketchbook, I use the automatic process to create my drawing, a process often used by surrealist artists. You don’t plan your drawings, you just let your mind run free through the pencil. When I first discovered Islamic miniatures, they seemed so daring. I was taught as a child that Muslims should not display pictures of animals or people and I have a vivid memory of coming home from school one day and a friend of the family had taken down all my art blue tacked to my bedroom wall. The book format allowed figurative miniatures to thrive because the viewer could choose to gaze upon them, unlike wall art. I think this was one of the reasons why I chose to specialise in book illustrations. I also love the aesthetics of miniatures, the multiple perspectives, the colours, the disjointed figures.

Do you have any advice for people who want to start working on their own graphic novels?

I think it’s worth working on a small comic first to figure out your own process and there will be many things you learn from creating your first one. Then you might decide that writing isn’t for you or you don’t enjoy illustrating because of how time-consuming it is (at least it is for me) so you could collaborate with someone for your next project. The other reason I would advise to start small is that creating a graphic novel takes a lot of time and energy, so you are better off having a finished project than working on a lengthy story but never getting around to finishing it.

Tell us about your most favourite part in “Mongrel”.

My favourite spread is where Shuna has her head on her mother’s, Amma’s, lap. Amma is stroking Shuna’s hair, displaying tenderness whilst teaching her about Shaitan and telling her off about being lazy in a formidable tone. This spread embodies the complexity of Shuna’s and Amma’s relationship as Amma feels that it is her duty to push her daughter to be a pious Muslim girl through her strict parenting, but the affection between mother and daughter cannot be ignored. I’m pleased with the composition of this page too, with how all the panels pull together.

What memorable responses have you had with your work?

The responses which have stuck with me are the ones where people tell me how much it resonated with them and bought to the surface memories growing up as a British Muslim. I feel that it opens people up to me because I have been so frank about things that are usually kept quiet within British-Bangla Muslim community. I’ve become very good friends with someone who initially messaged me via my art page telling me that they felt my story was their story. We ended up reminiscing together and reflecting on society, culture and religion. This was 2 years ago and we still talk regularly.

Tell us about your protagonist “Shuna”.

Shuna is my alter-ego. She is the body I use to create distance between myself and the story. By stepping aside and making Shuna the protagonist, I can reflect on her actions and her thoughts in a more objective way as they are no longer mine but hers.

Shuna faces quite typical challenges for a young Muslim girl, she wants to be a good Muslim and please her parents, but she also wants to fit in on the social scene and go to parties. Some of Shuna’s experiences are atypical because she is a white Muslim and her father is a convert to Islam.

How did you develop the aesthetics of your book?

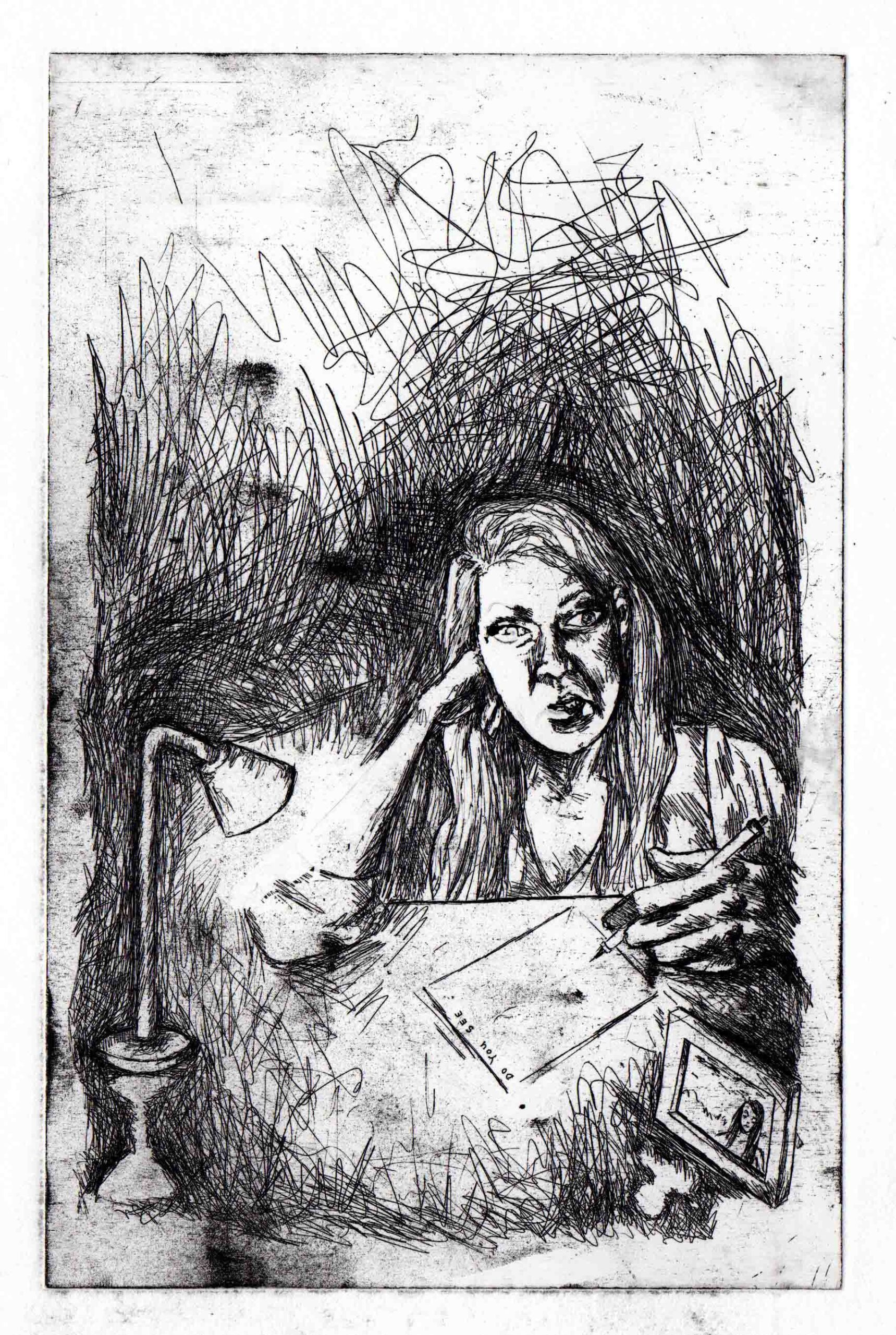

The aesthetics of the book was developed whilst I was studying on the MA. I spent months experimenting with different mediums and processes to try and get the look of Mongrel right. My mark-making before Mongrel was quite controlled, but I was inspired by an etching I created to push my mark-making to be more expressive. I also used to draw figures to be anatomically correct, this was something I wanted to change to create the Mongrel world.

What mediums are you most comfortable working with?

I’m comfortable working with any 2D medium, pencil, paint or digital. In the future, I would like to experiment with creating 3D art. It has been many years since I have used clay.

Professionally, what are your goals?

My dream job is to illustrate alongside teaching illustration at a post-compulsory level. I hope to start writing my second graphic novel soon.